The Cultural Roots of Crime

犯罪的文化根源

A conversation about the rise and fall of violence in America with criminal-justice scholar Barry Latzer.

——与刑事司法学者Barry Latzer就美国暴力犯罪起落的对话

Barry Latzer is that rare academic with both practical and theoretical knowledge of his subject matter. He prosecuted and defended accused criminals while teaching at the City University of New York graduate center and John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His new book, The Rise and Fall of Violent Crime in America, makes use of more than a century of crime statistics to sum up the wisdom of a long career studying why crime waves rise and fall. It’s a book that does not shy from the controversial, as you’ll see from our conversation.

Barry Latzer是少数在自己的专业领域内同时拥有实践和理论知识的学者之一。在纽约市立大学研究生中心和约翰·杰伊刑事司法学院任教的同时,他还对被指控的罪犯提起诉讼或为之辩护。他的新书《美国暴力犯罪的起落》用了一个多世纪的犯罪数据积累起一位从业者对暴力犯罪浪潮为何起落的深刻洞见。从我们下面的对话中你会看到,这是一本对争议话题毫不避讳的著作。

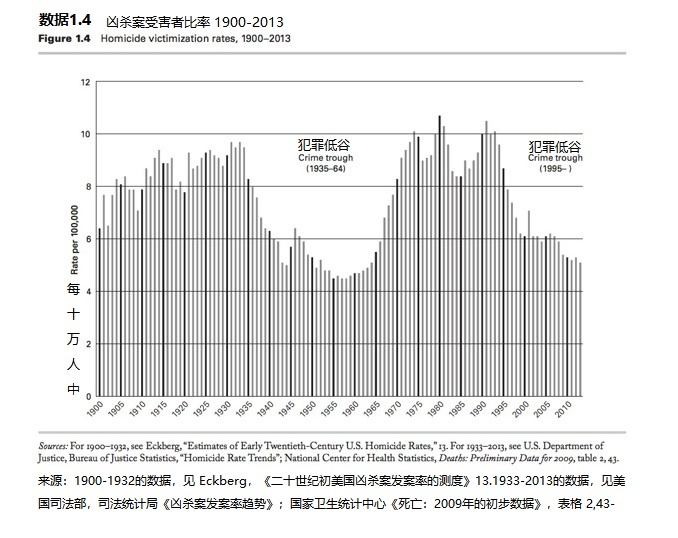

David Frum: Your book ends with the ominous possibility that the great crime reduction since the early 1990s is not a permanent transition, but just a temporary trough in a recurring cycle of crime spikes and crime drop-offs. Could you briefly explain the basis of this worrying claim?

David Frum:你书的结尾给出了这样一个预言:自1990年代初期开始的犯罪率下降趋势不是永久的,而是反复发生的犯罪高潮和低谷之间一个暂时的低谷。你能简单解释下这一令人忧虑的说法的基础吗?

Barry Latzer: The optimistic view is that the late ‘60s crime tsunami, which ended in the mid-1990s, was sui generis, and we are now in a period of “permanent peace,” with low crime for the foreseeable future. Pessimists rely on the late Eric Monkkonen‘s cyclical theory of crime, which suggests that the successive weakening and strengthening of social controls on violence lead to a crime roller coaster. The current zeitgeist favors a weakening of social controls, including reductions in incarcerative sentences and restrictions on police, on the grounds that the criminal-justice system is too racist, unfair, and expensive. If Monkkonen were correct, we will get a crime rise before long.

Barry Latzer:乐观的看法是,始于1960年代晚期终于1990年代中期的犯罪浪潮只是一个特例,我们现在正身处一个“永久的和平时期”,在可预见的未来犯罪率都会很低。悲观主义者则相信Eric Monkkonen关于犯罪率的周期理论,该理论指出,长时间跨度内社会对暴力的控制力时强时弱,从而导致犯罪率曲线如过山车般起伏。当下的时代潮流偏向于社会控制的减弱,包括减少拘禁判决和放松政策限制,而其思想背景是认为刑事司法系统太种族主义、太不公平和太昂贵。如果Monkkonen是正确的,我们不久便会看到犯罪率的上升。

Optimists point to the absence of factors that brought on the 60s crime boom: no immigration or migration of high-crime populations, no demographic upsurge in the youth population. They might also add: continued movement of minorities to the middle class, and no drug epidemics (like crack cocaine) among poor populations, which generate spikes in violent crime. (The current heroin/opioid crisis is unlikely to produce significant violent crime so long as the drugs are cheap and the users relatively affluent. Drug and alcohol prohibitions produce violence in two ways: where distribution gangs compete for territory and kill one another, and where poor populations are unable to support their addictions, leading to robbery and other crimes to raise money.)

乐观主义者强调,导致60年代犯罪率高企的因素已经不复存在:高犯罪率人群的移民潮和人口迁徙没有了,人口统计曲线上年轻人的高峰已经过去。他们也许还会加上如下有利因素:少数族裔持续成为中产阶级,曾经导致犯罪率飙升的毒品(比如可卡因)在穷人中的泛滥不存在了。(只要海洛因和类鸦片仍旧便宜并且他们的使用者仍相对富裕,当下的毒品危机就不太可能导致重大的暴力犯罪。毒品和酒精禁令通过两种方式催生暴力:贩卖的黑帮集团为了地盘相互厮杀;上瘾的穷人为了购买毒品便会去进行抢劫和其它犯罪活动。)

Frum: Maybe we can get some perspective on today’s crime situation by more closely examining the previous peak, 1890-1935, and the previous plunge, 1935-1965. Why in your estimation did crime spike so high in that first period and drop so deep in the second?

Frum: 也许通过仔细审视犯罪率曲线达到高峰的1890-1935年和发生陡降的1935-1965年,我们可以得到对今天的犯罪情势的一些洞见。在你看来,犯罪率在前一阶段陡然上升而又在后一阶段深度回落的原因是什么?

Latzer: I wouldn’t date the start of the first 20th century crime boom at 1890. The 1890s were a low-crime period in the big cities of the North. In the South, however, black violent crime rose and rural whites panicked, leading to the lynching and convict lease policies of that era. Northern cities started to suffer more violent crime in the first decade of the 20th century, partly because of the southern Italian migration to the U.S. The typical Italian immigrant crimes were murder, assault and threats of same by the so-called Black Hand, a proto-Mafia which mainly terrified the immigrants themselves.

Latzer: 我不会把1890年当作20世纪第一场犯罪浪潮的发端。北方的大城市在1890s年代犯罪率很低。然而在南方,黑人暴力犯罪增加而引发乡村白人的恐慌,导致了私刑和罪犯租赁政策(convict lease policies)在该地区的流行。北方的城市从1910年代开始遭受暴力犯罪的侵扰,部分源于南方意大利人的迁入。典型的意大利移民犯罪包括谋杀、人身侵犯和由所谓的黑手党、意大利帮派发出的暴力和死亡威胁,这些帮派主要恐吓的是移民自己。

Then, following World War I, a Mexican migration to the U.S. added to the crime totals, as did a major spike in black migration out of the South. The war sparked a black movement to big cities for economic betterment, but, unfortunately, also brought with it high crime rates within the black community. In addition, Prohibition, which began in 1920, produced violence among the alcohol distribution gangs competing for turf (though this violence did not target ordinary citizens).

之后,随着一战爆发,墨西哥移民的到来增加了犯罪总量,就像从南方来的黑人移民高峰一样。战争点燃了一场黑人为了追求经济状况改善而向大城市迁徙的运动,但不幸的是,也带来了黑人社区内部的高犯罪率。另外,1920年的禁酒令导致了贩酒帮派之间的暴力冲突,他们为了争夺地盘而大打出手(虽然并不针对城市的原有居民)。

Violent crime peaked in the early 1930s, with a wave of bank robberies by “Pretty Boy” Floyd, “Baby Face” Nelson, John Dillinger, and Bonnie and Clyde Barrow. This was accompanied by the sensational kidnap-murder of the Lindbergh baby in 1932 and a spate of copycat kidnappings. J. Edgar Hoover made his name by directing the Federal Bureau of Investigation to hunt down and capture or kill these “Public Enemies,” as he labeled them, and by 1934 the FBI or local agents had successfully done so with each of them.

暴力犯罪的高峰在1930年代初到来,当时“漂亮男孩”Floyd、“娃娃脸”Nelson、John Dillinger、Bonnie和Clyde Barrow实施了一系列银行劫案。随之而来的还包括震惊世人的“林登伯格孩童绑架案”和受其启发而掀起的一股绑架浪潮。约翰·埃德加·胡佛指挥联邦调查局追查、逮捕和杀死这些“全民公敌(他本人语)”,他也因此声名鹊起。到1934年,FBI和地方执法机构已经成功地消灭了这些人。

Crime rates started to decline in the mid-1930s, at the same time that the New Deal went into effect. This may seem like cause-and-effect: unemployment and poverty were reduced, so violent crime diminished. But this is not necessarily correct. First, Prohibition ended in 1933, and that helped reduce murder rates. Second, the spate of bank robberies and kidnappings declined, partly because law enforcement apprehended high-profile perpetrators. Third, migration by blacks and Mexicans and immigration by Italians declined dramatically when jobs became unavailable due to the Depression. Finally, there was a severe downturn in the economy in 1937 and 1938, yet violent crime continued to fall. The American public was terribly damaged by the Great Depression—68 percent of Americans were below the poverty line in 1939—but this produced no increase in violent crime.

1930年代中期犯罪率开始下降,同时“罗斯福新政”开始推行。这看起来像是前因后果:失业率和贫穷得到遏制,所以暴力犯罪便消失了。但实际上可能另有原因。其一,1933年禁酒法被废除了,这有助于谋杀率的下降。其二,银行劫案和绑架案浪潮的消退部分源于执法部门逮捕了那些高调的罪犯。其三,大萧条导致工作不好找,于是黑人和墨西哥人的人口迁移及来自意大利的移民减少了。最后,1937年至1938年经济严重下滑,暴力犯罪仍继续减少。美国公众被大萧条严重伤害——1939年68%的美国人处于贫困线以下——但这并没有导致暴力犯罪的增加。

During World War II, crime continued to drop, partly because the war removed hundreds of thousands of young men from the streets to the barracks. When the war ended there was a brief spike in violent crime, but the downturn continued after the war and well into the postwar boom of the 1950s. No one is sure why crime remained low in the 1950s, but several factors helped. Crime rates for African Americans, though higher than average, were historically low for that community. Drug and alcohol use also were down. The Depression had produced a birth dearth, so the young male population was reduced. And the supercharged economy created a massive and growing middle class in a short period of time; and middle-class people seldom commit crimes of violence. All in all, the 1950s was a golden age of low crime.

二战期间,犯罪率继续下降,部分原因是成千上万的年轻人离开街头被送往营房。当战争结束,曾出现过一个短暂的暴力犯罪急升期,但犯罪率在战后持续下降并在1950年代的繁荣中保持了这种势头。没人确切知道为何犯罪率在1950年代保持了低水平,但一些因素起了作用。尽管非洲裔美国人的犯罪率高于平均水平,但其社区的犯罪率当时处于历史低点。当时毒品和酒精的使用也在降低。大萧条导致了出生率的下降,因此年轻男性的数量也下降了。活力充沛的经济在短时期内造就了庞大且不断壮大的中产阶级,而中产阶级很少实施暴力犯罪。总的说来,1950s年代是低犯罪率的黄金年代。

Frum:That answer showcases the most provocative feature of your book: your belief that different cultural groups show different propensities for crime, enduring over time, and that these groups carry these propensities with them when they migrate from place to place. As I don’t have to tell you, this idea and its implications stir more controversy among criminologists than any other. Would you state your position as precisely as possible in this brief space? I’ll then review some of the objections and ask you to answer them.

Frum:刚才的回答显示了你的新书最得罪人的一点:你相信不同的文化族群显示出持久且不同的犯罪倾向,这些族群带着各自的倾向从一地迁移到另一地。我想不用我来告诉你,这个看法和其暗含意味在犯罪学家中激起的争议甚至大于在其他人群中引起的争议。在这里你能尽可能精确地阐述一下你的立场吗?我稍后会提到几个反对意见并请你作答。

Latzer: First of all, culture and race, in the biological or genetic sense, are very different. Were it not for the racism of the 18th and 19th centuries, we might not have had a marked cultural difference between blacks and whites in the U.S. But history cannot be altered, only studied and sometimes deplored.

Latzer:首先,从生物学和遗传学的角度看,文化和种族是十分不同的。要不是18、19世纪的种族主义,在今天的美国,黑人与白人也许不会有如此显著的文化差异。但历史不可能被修改,只能被研究,有时则被谴责。

Different groups of people, insofar as they consider themselves separate from others, share various cultural characteristics: dietary, religious, linguistic, artistic, etc. They also share common beliefs and values. There is nothing terribly controversial about this. If it is mistaken then the entire fields of sociology and anthropology are built on mistaken premises.

不同的人群相互区别,正如他们认为的那样,他们拥有多种多样的文化特性:饮食、宗教、语言、艺术等等。他们也共享相同的信念和价值。关于这点,没有什么了不起的争议。如果在这一点上犯错,那么社会学与人类学的整个基础都建立在错误的前提上。

If cultural differences don’t explain this, then what does?

如果文化差异不能解释这一点,那么什么可以?

With respect to violent crime, scholars are most interested in a group’s preference for violence as a way of resolving interpersonal conflict. Some groups, traditionally rural, developed cultures of “honor”—strong sensitivities to personal insult. We see this among white and black southerners in the 19th century, and among southern Italian and Mexican immigrants to the U.S. in the early 20th century. These groups engaged in high levels of assaultive crimes in response to perceived slights, mainly victimizing their own kind.

针对暴力犯罪,学者们对族群就作为解决个人冲突方式的暴力行为的偏好特别感兴趣。传统上,一些乡村族群会发展出“荣誉文化”——对个人侮辱强烈敏感。我们在19世纪的南方白人和南方黑人身上都可以看到这一点,同样也包括20世纪初移民美国的南方意大利人和南方墨西哥人。这些族群回应轻慢的方式是攻击性的犯罪,受害者大多是他们的同类人。

This honor culture explains the high rates of violent crime among African Americans who, living amidst southern whites for over a century, incorporated those values. When blacks migrated north in the 20th century, they transported these rates of violence. Elijah Anderson’s book, The Code of the Streets, describes the phenomenon, and Thomas Sowell, in Black Liberals and White Rednecks, helps explain it.

这种荣誉文化解释了非洲裔美国人中的高暴力犯罪率,他们同南方白人一起生活了一个多世纪,已经将这种价值观内化了。当黑人在20世纪迁移到北方后,他们也带来了这种暴力犯罪的高发率。Elijah Anderson的著作《街头法则》描述了这种现象,而Thomas Sowell的《黑人红脖和白人李泊儒》则有助于解释这种现象。【译注:原文中为《Black Liberals and White Rednecks》,应是笔误。此书名应为《Black Rednecks and White Liberals》。】

In the case of blacks, the big change in terms of violence was the high robbery rates and the concomitantly high white victimization rates of the post-60s era (robbery being a crime against strangers). These were products of the massive postwar spike in black migration to northern cities (800,000 in the 1960s; 1.8 million in the ‘70s); the black baby boom coming of age for violence (late adolescence, early manhood); a youth crime contagion, in which crime became cool and young males copied one another and began mugging with impunity; and the opportunities for victimization presented by whites who moved about northern cities with lots of cash and valuables.

说到黑人,其暴力行为的最大变化是60年代后的高抢劫率和与之相伴的白人高受害率(抢劫是一种针对陌生人的犯罪)。导致这些后果的因素包括:战后大规模的黑人迁移潮(1960年代有80万黑人迁往北方城市,70年代这个数字为180万);黑人婴儿潮一代进入热衷暴力的年龄(青少年后期,刚成年时);年轻人中的犯罪流感让受感染的年轻人觉得犯罪很酷,小伙子们相互模仿并开始行凶抢劫而不受惩罚;带着大量现金和值钱之物的白人搬到北方城市也增加了他们成为受害者的可能。

Theories of crime that point to poverty and racism have the advantage of explaining why low-income groups predominate when it comes to violent crime. What they really explain, though, is why more affluent groups refrain from such crime. And the answer is that middle-class people (regardless of race) stand to lose a great deal from such behavior. Wisely, more affluent people go to law and seek other nonviolent methods to resolve interpersonal conflicts. Poor people, and especially young, male poor people, do not. Their perceived stake in the established order is tenuous.

在解释为何低收入人群占暴力罪犯中的绝大多数时,指向贫穷和种族主义的犯罪理论拥有优势。但它们其实只是解释了为何比较富裕的人群能克制自己不进行暴力犯罪。答案就是中产阶级(无论其种族)施行暴力犯罪的代价巨大。更富裕的人群在遭遇人际冲突时会明智地寻求法律和其它非暴力的解决方式。穷人,尤其是年轻的男性穷光蛋则不会。他们在已经建立的社会金字塔中感觉不到自己有多少筹码。

The cultural explanation for violence is superior to explanations that rest of poverty or racism, however, because it can account for the differentials in the violent-crime rates of groups with comparable adversities. My favorite illustration of this is the Haitian situation in 1980s Miami. Here was a group of black people coming to the U.S. illegally in makeshift boats. They had a brutal history of slavery, and were illiterate in English, impoverished, and unwelcome. Yet their violent-crime rates were much lower than those of African Americans living in the same city in the same time period. If cultural differences don’t explain this, then what does?

对暴力而言,文化上的解释要比其他诸如贫穷、种族主义等解释更优,因为它解释了处在相似困境中的群体为何拥有不同的暴力犯罪率。对此,我最喜欢用1980年代迈阿密的海地人来举例。当时有一帮黑人乘坐简陋的船只非法到达美国。他们经历过残酷的奴隶生活,不懂英语,一贫如洗,而且不受欢迎。但是他们的暴力犯罪率却比同时期的、同座城市的非洲裔美国人要低得多。除了文化差异还有什么能解释这种现象?

Frum: Let’s flash forward to the present day. You make short work of most of the theories explaining the crime drop-off since the mid-1990s: the Freakonomics theory that attributes the crime decline to easier access to abortion after 1970; the theory that credits reductions in lead poisoning; and the theory that credits the mid-1990s economic spurt. Why are these ideas wrong? And what would you put in their place?

让我们回到当下。你为大部分试图解释1990年代中期以来犯罪率下降的的理论做过概述:《魔鬼经济学》理论——将犯罪率下降归功于1970年后日益普及的流产;将(犯罪率)下降归因于铅中毒减少的理论;以及归功于1990年代中期经济繁荣的理论。为什么这些看法是错的?你又作何解释呢?

Latzer: The abortion theory has suffered some very serious methodological criticisms of late, leading to damaging concessions by Steven Levitt. But aside from this, both the abortion and leaded-gasoline theories are mistaken because of a failure to explain the crime spike that immediately preceded the great downturn.

Latzer: 堕胎理论近来遭到一些严峻的方法论上的批评,导致Steven Levitt【译注:《魔鬼经济学》作者,堕胎理论的主要倡导者。】做出动摇其理论的重大让步。不过抛开这个不谈,不管是堕胎还是铅中毒理论都是错误的,因为它们不能解释在紧邻经济大衰退之前的年份犯罪率高涨。

Abortions became freely available starting in the 1970s, which is also when lead was removed from gasoline. Fast-forward 15 to 20 years to the period in which unwanted babies had been removed from the population and were not part of the late adolescent, early adult, cohort. This cohort was responsible for the huge spike in crime in the late 1980s, early 1990s, the crack cocaine crime rise. Why didn’t the winnowing through abortion of this population reduce crime? Why did young people instead generate a major crime increase?

从1970年代开始,堕胎逐渐成为一个可选项,汽油中的铅也是在这时被去除。将时间从此时快进15到20年,在这段时间里意外怀上的孩子被引产,这些孩子本来会成为青春期的小伙子们的一部分。这一时期的年轻人要为1980年代末和90年代初的显著犯罪高峰、可卡因犯罪的抬头负责。为什么当时堕胎的推广没能降低犯罪率呢?为什么那一代年轻人反而催生了犯罪率的明显上升?

The abortion theory is unable to explain this. Instead, it focuses on the crime decline that began in 1993. Likewise, the lead removal theory. The same “lead-free” generation that engaged in less crime from 1993 on committed high rates of violent crime between 1987 and 1992. Incidentally, there was plenty of lead in gasoline in the 1950s and early 60s when violent crime was low.

堕胎理论没能对此作出解释,相反,其只是关注从1993年开始的犯罪率下降。同样,铅去除理论与之类似。同样免受铅毒害的一代人,在1987年到1992年间制造了高犯罪率,却在1993年较少犯事。巧的是,1950年代和60年代早期汽油中含有大量铅,但当时的暴力犯罪却很少。

As for economic booms, it is tempting to argue that they reduce crime on the theory that people who have jobs and higher incomes have less incentive to rob and steal. This is true. But violent crimes, such as murder and manslaughter, assault, and rape, are not motivated by pecuniary interests. They are motivated by arguments, often of a seemingly petty nature, desires for sexual conquest by violence in the case of rape, or domestic conflicts, none of which are related to general economic conditions. Consequently, violent crime rates may decline in periods of recession, such as the 1890s, 1930s or 2007-2009, while rising in boom eras, such as the 1920s and late 1960s.

说到经济繁荣,人们很容易认为犯罪的减少与此有关。背后的理论是,有工作和较高收入的人缺少去抢去偷的激励。这是正确的。 但是暴力犯罪,如蓄意谋杀、误杀、人身攻击和强奸,不是由金钱利益驱动的。导致这些暴力犯罪的通常是出于微不足道的起因的争吵,在强奸案中是对通过暴力获得性征服的渴望,或是家庭内部矛盾,这些都跟经济状况不相干。因此,暴力犯罪率可能在经济衰退时下降,例如1890年代、1930年代或是2007~2009年;同样也可能在经济繁荣的时代上升,比如1920年代和1960年代后期。

Rises in violent crime have much more to do with migrations of high-crime cultures, especially to locations in which governments, particularly crime-control agents, are weak. Declines are more likely when crime controls are strong, and there are no migrations or demographic changes associated with crime rises.

犯罪率的升高同高犯罪文化的移民更有关系,尤其当某地的政府,特别是打击犯罪的部门力量羸弱时。当对犯罪的管控强有力时,犯罪率往往就会下降,而且在这种情况下,移民或人口结构的变化并未伴随着犯罪率的上升。

In the middle 1990s, the sudden end of the crack cocaine era set off the most recent crime trough. Crack was a youth contagion, a massive copying phenomenon, that ended as suddenly as it had begun. It ended because law enforcement clamped down on drug violators and drug-gang distributors, because the drugs were extremely destructive to the health and well-being of the users, and, mainly, because crack suddenly became uncool—a positive contagion.

1990年代中期,可卡因热潮的突然终结导致了最近一次犯罪率低谷。吸食可卡因是年轻人中的一种传染病,一种竞相效仿的现象,来得快也去得快。该风潮之所以结束是因为执法部门打压了违法使用毒品的人和贩毒团伙,因为该毒品对吸食者的身心健康危害实在太大了。另一个主要原因是,吸食可卡因突然变得不酷了——一种正面的流行病。

But the entire crack crime rise, from roughly 1987 to 1992, was a surprise in that violent crime had begun to fall in the early 1980s when the baby boom generation started aging out of violence. Only in the late 80s, when the boomer offspring began using crack, did crime rise once again. This surge lasted but six years, whereupon the decline resumed.

不过从大约1987年到1992年的整个可卡因犯罪的猖獗可算是一种意外,因为暴力犯罪从1980年代初开始便开始减少,当时婴儿潮一代开始越过热衷暴力的年纪。仅仅到了80年代晚期,婴儿潮一代的子女们开始吸食可卡因,犯罪率才再次开始上升。这股犯罪潮持续了仅仅六年,之后犯罪率再次下降。

In short, the aging of the violent boomer generation followed by the sudden rise and demise of the crack epidemic best explains the crime trough that began in the mid-1990s and seems to be continuing even today. Contrary to leftist claims, strengthened law enforcement played a major role in the crime decline. The strengthening was the result of criminal-justice policy changes demanded by the public, black and white, and was necessitated by the weakness of the criminal justice system in the late ‘60s.

简而言之,婴儿潮一代的逐渐老去和之后突然出现又消失的可卡因热潮很好地解释了从1990年代中期开始的、似乎一直持续到今天的犯罪率低谷。与左派宣称的相反,执法力量的强化在这次犯罪率下降中扮演了重要的角色。这种强化是民众(包括黑人和白人)呼吁的政策转变的结果,是60年代后期刑事司法体系的软弱导致的必然反弹。

On the other hand, conservatives tend to rely too much on the strength of the criminal-justice system in explaining crime oscillations, which, as I said, have a great to do with migrations and demographics. Still, weak law enforcement has been responsible for a great deal of violence—in the 19th century South and “Wild West,” and in the North in the late 1960s. The contemporary challenge is to keep law enforcement strong without alienating African Americans, an especially difficult proposition given the outsized violent-crime rates in low-income black communities.

另一方面,保守派倾向于过分强调刑事司法体系的力量来解释犯罪率的起伏,而如我说的,这其实同移民和人口结构有很大关系。诚然,执法力量的薄弱要为19世纪南方和“狂野西部”的、以及1960年代后期北方的暴力犯罪负很大责任。当时的挑战是,在不疏远非洲裔美国人的同时保持有力的执法,考虑到当时低收入黑人社区惊人的暴力犯罪率,这非常困难。

Frum: The sad exception to the downward trend in crime since 1990 is the apparent increase in mass shootings—like the atrocity in Orlando, where a shooter apparently motivated by Islamic ideology killed 49 in a gay nightclub. Should such attacks be included in our thinking about crime? If so, how should we think about them?

Frum:1990年以来犯罪率的下降趋势面临一个可悲的例外:大规模枪击案明显增多——比如发生在奥兰多的惨剧,一个明显受到伊斯兰意识形态鼓动的枪手在一个同性恋酒吧开枪打死了49人。当我们思考犯罪问题时,这类袭击事件应该被考虑进去吗?如果是的话,我们应该如何考虑此类事件?

Latzer: If mass killings are defined as four or more victims per incident, then, like ordinary crime, mass killings are a product of quarrels, anger, and the ready availability of firearms because seven out of 10 occur in a private residence. Mental illness and substance abuse may also be factors. If we separate out the ideologically motivated mass killings, such as Orlando (apparently) and San Bernardino, then we have a different problem.

Latzer:如果大规模枪击案(mass killings)被定义成一次有超过四名受害者的事件,那么就像普通的犯罪,大规模枪击案是争吵、愤怒和可即时获得武器的后果,因为七成案件发生在私人居所。精神疾病和药物滥用也可能是原因之一。如果我们把意识形态驱动的大规模枪击案单独区分出来,比如奥兰多事件(明显的)和圣贝纳迪诺事件【译注:2015年12月2日,美国加利福尼亚州的圣贝纳迪诺发生了一起枪击案,造成14人死亡、21人受伤。凶手之一的赛义德·法鲁克是穆斯林。】,那么这是另一个不同的问题。

Surveilling potential killers who share a violent ideology will be extremely difficult but worthwhile. Limiting the availability of rapid-fire weapons with high-capacity ammunition clips is also worth doing, but politically divisive. And, of course, developments abroad will affect the number of incidents, as will the copycat effect in the immediate aftermath of an incident. This is a complex problem, different from ordinary killings, which, by the way, take many more lives

监视那些有暴力意识形态的潜在凶手会非常困难,但确实值得。限制配有大容量弹夹的速射武器也是值得的,但在政治上存在争议。当然,国外形势的发展也会影响事件的数量,一次事件后的模仿效应同样如此。这是个复杂的问题,不同于普通的杀人事件,顺便提一下,后者造成更多的命案。

翻译:@Drunkplane-zny(@Drunkplane-zny)

校对:混乱阈值(@混乱阈值)

编辑:辉格@whigzhou comments powered by Disqus