Long-term relative age effect: Evidence from Italian football

长期相对年龄效应:来自意大利足球的证据

A vast cross-discipline literature provides evidence that — in both education and sports — the youngest children in their age group are usually at a disadvantage because of within-group-age maturity differences, known as the 'relative age effect'. This column asks whether this effect could last into adulthood. Looking at Italian professional footballers' wages, the evidence suggests that the relative age effect is inescapable.

大量的跨学科文献表明:在教育和体育领域,由于组内相对成熟程度的差别,同年龄组内最年轻的孩子常处于不利地位。这一现象被称为"相对年龄效应"。本文探讨了这种效应是否能持续到成年。通过对意大利职业足球运动员薪资的调查,结果发现此相对年龄效应是无法摆脱的。

What are the consequences of the relative age effect? For example, relatively young pupils (i.e. the youngest pupils in their age group) are more likely to be held back in school (Dixon et al. 2011) and receive lower grades (Bedard and Dhuey 2006, Ponzo and Scoppa 2014, Navarro et al. 2015). They also are more likely to be diagnosed with a learning disability (Dhuey and Lipscomb 2009) and with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Zoëga et al. 2012).

相对年龄效应的后果是什么?举个例子,相对更年幼的学生(例如那些在同年龄范围内最年轻的)更容易留级与得到低分。这些相对年幼的学生更容易被诊断为学习障碍和注意力缺陷或多动症。

Could the relative age effect last into adulthood? Could people receive different wages because of childhood within-group-age maturity differences? Could people who suffered from adverse relative age effect in childhood be under-represented in top job positions? This column discusses some possible answers.

那么这些相对年龄效应是否会持续到成年?这些童年时期的相对成熟度差别是否会影响到未来薪资?那些在童年时遭受相对年龄效应劣势的人是否更少出现在顶尖的工作职位中?本文讨论了一些可能的答案。

The path towards a long-term relative age effect

通往长期相对年龄效应之路

Children are usually grouped based on a relevant 'cut-off date' – in these groups, some children are relatively older than others, which causes maturity gaps and therefore performance gaps between them. For example, in some European countries, the age-grouping system in school is based on the calendar year (i.e. the cut-off date is 1 January) and children start school in September in the year when they turn six years old. In the first class, there are some children who are six before school starts (i.e. born in January-August) and others who turn six after school has started (i.e. born in September-December).

通常根据某一截断日期,孩子们会被分成不同年级组。在这些年级组内,一些孩子相对年长于其他孩子,这导致了其间的成熟度差异以及进而在表现上的差异。例如在一些欧洲国家,学校的年级系统是基于年历的(即以1月1日划分不同年纪),孩子们在到达6岁的那年9月开始上学。于是在第一节课上,有一些孩子在课程开始时候就已经到达6岁了(1月到8月出生的孩子们),而另一些孩子则会在课程开始之后才到达6岁(那些9月到12月出生的孩子)。

Consider the difference in maturity between children born in the two extreme months – pupils born in January are about 17% older than pupils born in December. This large maturity gap causes a performance gap – the relative age effect.

想象一下1月份生的学生和12月份生的学生的成熟度差异——前者要比后者年长17%。这一巨大的成熟度差异会导致表现上的差异,即相对年龄效应。

Although the relative age effect is initially caused by a pure maturity gap, social factors influence its magnitude and could provoke its persistence. In education and sport activities, children might be streamed (e.g. they are tracked into different learning/training paths) and/or selected (e.g. they are chosen to participate in optional after school classes or to play in their soccer team's starting lineup) based on their perceived skills. Furthermore, streaming and selection are affected by the level of competition between kids (e.g. there is a limited and pre-established number of spots for after school classes or in starting lineups of soccer teams).

虽然相对年龄效应最开始是单纯地由成熟度差异造成的,但社会因素会影响其程度并引发其持续性影响。在教育和体育活动中,基于孩子所表现出的能力,孩子们可能会被分配(例如被分到不同的学习或训练方式)或/并选拔(例如被挑选入课外班或进入足球队名单)。反过来,这些分配和选拔又会为孩子之间的竞争程度所影响(例如课外班和预备队总是有预定的人员限制)。

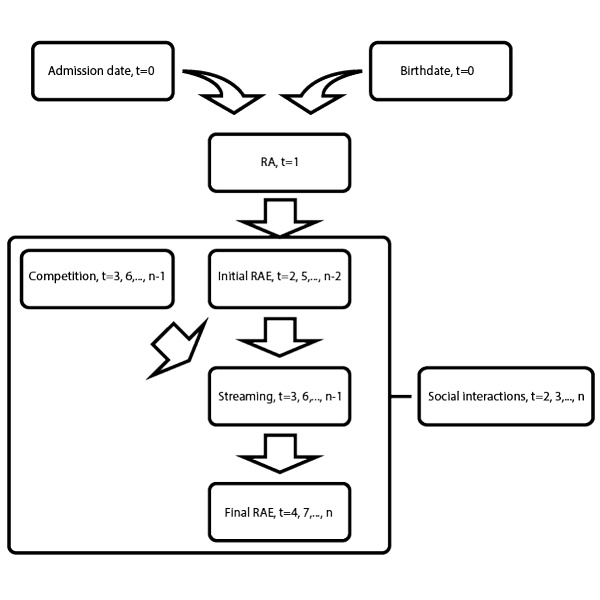

Finally, the whole process is affected by interactions (e.g. the Pygmalion effect, see Hancock et al. 2013 – soccer trainers will provide special attention to those children whom they perceive are more talented, who as a result become more talented due to this greater attention). The process that affects the initial relative age effect can be summarised in Figure 1, taken from Fumarco and Rossi (2015).

最终,这整个过程会被交叉影响(例如皮格马利翁效应:足球教练会对那些被发现更有天赋的孩子加以特殊关注,反过来导致这些孩子由于此特殊关注变得更优秀)。这一对初始相对年龄效应的影响过程被总结在图1中。

Figure 1. Process affecting initial relative age effect

【图1:影响初始相对年龄效应的过程】

This process could lead to a possible long-lasting relative age effect, and therefore could be visible even when initial maturity differentials disappear. In particular, paraphrasing Cascio's (2008) paper – long-lasting relative age effects are likely to occur when children are streamed and selected based on perceived skills since the beginning of their training or education.

此过程可以导致一种长期存在的相对年龄效应,甚至可以在成熟度差异消失的时候依旧可见。根据 Cascio在2008年的文章,长期相对年龄效应可能从训练和教育活动最开始的分组选拔时就出现了。

Evidence of a long-term relative age effect

长期相对年龄效应的证据

Studies that investigate the existence of a relative age effect in adulthood are limited and often display discordant results. Some studies do not find evidence of a relative age effect on wages (e.g. Crawford et al. 2013, Larsen and Solli 2012). Other studies provide evidence of a negative relative age effect on wages and employment rates (e.g. Peña 2015, Black et al. 2011, Plug 2001). Results are also contradictory when the focus shifts to the relative age effect on tertiary education performance. Roberts and Stott (2015) find that students born toward the end of the selection year perform better and Peña (2015) finds that relatively older students graduate from college more frequently, whereas Kniffin and Hanks (2015) do not find any gap in the possibility to earn a doctoral degree. It is likely that one of the main reasons for not obtaining clear and coherent results on a long-term relative age effect is the lack of very detailed data.

调查相对年龄效应能否持续到成年的研究数量有限并且时常有不一致的结果。一些研究发现其对工资没有影响,而另一些研究则发现其对工资和就业率有负面的影响。当涉及高等教育, 这些结果甚至是相互矛盾的。Robers和Stott在2015年发现靠近年底出生的学生表现得更优异,而Peña在2015年发现相对年长的学生更容易从大学毕业,同时Kniffin和Hanks在2015年发现在获取博士学位的概率上,年长和年幼的人群并无差异。这些结果的不同可能是由于数据不够详实造成的。

The sports labour market provides a more suitable framework than that of the standard labour market and tertiary education system for studying long-term relative age effects because of the (often public) very rich data. Studies that use these data typically provide one result: because of streaming and selection, older athletes are over-represented in the population of athletes in any given tournament — for example, in top football leagues (Musch and Hay 1999), the Olympic Games (Joyner et al. 2013), and the NFL (Böheim and Lackner 2012).

由于能提供更详实的数据(经常是公开的),对于研究长期相对年龄效应,相比于传统的劳动市场和高等教育体系,运动员市场提供了一个更好的研究框架。基于此类数据的研究展示出了一个典型的结果:由于分组和选拔,在任何诸如顶级足球联盟、奥运会比赛、NFL联赛等锦标赛中,具有相对年龄优势的运动员都在相对数量上占有优势。

However, the sports literature has rarely explored possible long-term effects also in terms of wages. To contribute to this limited literature, in a recent paper (Fumarco and Rossi 2015) we investigate relative age effects on footballers' wages in a very large and detailed dataset, where players are followed over several seasons, in one of the most competitive football leagues – the top Italian league, Serie A.2

然而关于运动的文献很少研究相对年龄对薪资方面可能造成的长期影响。为弥补这一空缺,我们在2015年的一篇文章中调查了基于大量详细的顶级意大利足球联盟Serie A.2的足球运动员工资的相对年龄效应。在该研究中运动员们被长期跟踪调研,跨越数个赛季。

Relative age effects on representativeness and on wages of Serie A footballers

Serie A 球员人数和工资的相对年龄效应

The dataset contains information on all Italian players from seven consecutive Serie A seasons, 2007-08 to 2013-14, for a total of 508 Italian footballers who have played for at least one Serie A team over these seven seasons. In Serie A there are 20 teams – at the end of each season the last three teams are relegated, while the top three teams from the second league are promoted. We focus only on Italian players because information on age-group systems of other countries is difficult to retrieve, and we do not feel comfortable assuming that foreign Serie A players trained under the same cut-off date. In fact, we know from other studies that until the mid-1990s, different cut-off dates were adopted in different EU and non-EU countries, such as, Belgium, Germany, Australia and Brazil (1 August), Japan (1 April), and Great Britain (1 September, which is still the current cut-off date).

此数据包含了2007-08到2013-14赛季间,所有508名至少为一家Serie A球队效力的意大利球员的7个连续赛季的信息。在Serie A中总共有20支球队,在赛季结束时最后三名球队会被降级,而次级联赛的前三名会被升级。我们只关注来自意大利的球员,因为其它国家球员的年龄组别很难得到,而我们不能简单假设外国运动员采用了相同的年龄分级法。事实上,从其它研究中我们得知,直到1990年代不同的欧洲和非欧洲国家如比利时、德国、澳大利亚、巴西(采用8月1日作为分隔点),日本(采用4月1日)、英国(采用9月1日作为分隔点直至今日)分别采用了不同的年龄分隔日期。

In Italy, the cut-off date for the age-grouping system is 1 January (for complete details on the youth system, see Fumarco and Rossi 2015). In the presence of the relative age effect, players born soon after this date are expected to have enjoyed an advantage over relatively younger players born on dates approaching 31 December throughout their youth. This advantage could be reflected in at least two ways on Serie A players – distribution of players' birthdates (i.e. relatively older players could be over-represented in the population of Serie A Italian players, even if we account for the monthly birthrate of the Italian population) and wages (i.e. relatively older players could earn higher wages, which would imply persisting performance gaps). This is exactly what we have found in our study.

在意大利,年级系统的分隔日期是1月1日(更多细节可以产看Fumaraco和Rossi 2015年的文章)。在相对年龄效应的影响下,在整个青少年时期,此日期后不久出生的运动员被发现比临近12月31日出生的相对年幼的运动员更有优势。在Serie A的球员里,这一优势可能被反映在至少两个方面:球员的出生分布(即排除了意大利的出生月间差别后相对年长的球员在总意大利球员数所占中更多)和薪水(即相对年长的球员能够获得更高的薪资,这反映了其持续存在的表现差异)。而这正是我们在研究中所发现的。

Representativeness

人数

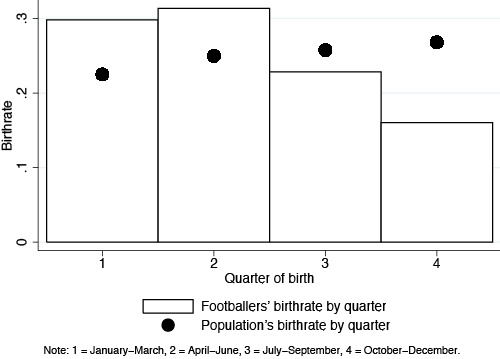

Figure 2 represents the distribution of quarters of birth among Serie A Italian players.

图二展示了Serie A联赛中意大利球员出生日期的按季分布情况。

Figure 2. Distribution of quarters of birth among Serie A Italian players

【图2:Serie A 意大利球员出生日期按季分布图】

The black dots represent average quarters of birthrates in Italy between 1965 and 1995 – this is the range of years of birth in our dataset. Clearly, players born in the first quarter are over- represented, second-quarter players are still over-represented but to a slightly lesser extent, third- quarter players are under-represented and fourth-quarter players are even more strongly under- represented. When we consider months in lieu of quarters, the trend is more striking (see Fumarco and Rossi 2015). This result seems to be strongly consistent throughout European countries, as illustrated in Poli et al. (2015) — in this study authors decide to assume uniformity in European cut-off dates.

黑点表示在我们的数据范围内,即1965到1995年间每季意大利的平均出生率。很明显,在第一季出生的球员人数与当季出生率比相对较多,第二季度出生的球员仍相对较多但比例有所下降,第三季度的球员数相对当季出生率较少,而第四季度的相对球员数明显更少。当我们用月份来代替季度时,这一趋势会更加明显(参见[Fumarco and Rossi 2015])。这一结果似乎适用于所有欧洲国家(参见Poli等人的2015年的论文。在其研究中作者假设了欧洲所有国家使用了相同的年龄分隔点)。

Wages

薪资

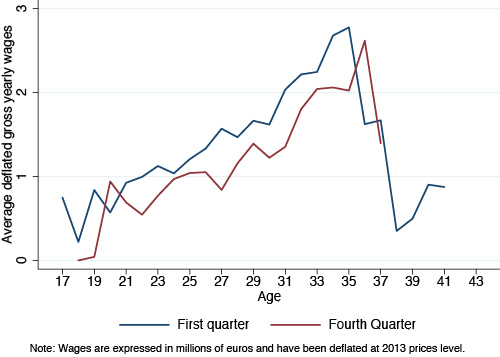

Figure 3 provides average gross yearly wages (deflated at the 2013 prices level) of Serie A Italian players born in the first and fourth quarter (the other two quarters are not reported for illustrative purposes).

图三展示了Seria A中意大利球员中生于第一季度和第四季度(为了视觉效果,另外两季度的数据未在此展示)的平均总年薪(折算致2013年的物价水平)。

Figure 3. Average gross yearly wages of Seri A Italian players

【图三:Seria A球员平均总年薪】

Clearly, relatively older players receive higher wages than relatively younger counterparts during most of their soccer career.

很明显,相对年长的球员在他们的整个足球职业生涯都比相对年轻的竞争者获得了更高的工资。

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate descriptive statistics, but their insights are confirmed by statistical methods of inference (see Fumarco and Rossi 2015).

图2和图3展示了描述性的统计数据,但其洞见也被统计学推断方法所印证了(详见[Fumarco and Rossi 2015]) 。

Possible remedies and further studies

可能的补救措施和未来的研究方向

These findings provide sound evidence for a long-term relative age effect in football, in terms of both representativeness and wages, which partially satisfies our initial questions. To remediate the existence of relative age effects in the Italian football, a reform of the age-grouping system could be carried out (e.g. a shortening of the chronological distance between oldest and youngest players in the same age group). Also, football coaches could be educated on this phenomenon so they can account for it when they train children. Combatting the relative age effect in soccer is important for the sake of equity, children's happiness, and additionally because it would reduce the waste of potentially skilled (but not yet mature) relatively younger players in youth categories.

这一发现为足球中的长期相对年龄效应在人员数和薪资方面提供了可靠的证据并部分回答了我们最初提出的问题。为了改变这一相对年龄效应的影响,可以对年龄分组系统进行改革(例如缩短各年龄组间的年龄范围)。同时,让足球教练通过了解此现象从而改进教学。消除相对年龄效应对于平等以及孩子们的快乐来说很重要。另外它还能减少对组内年轻球员潜在天赋的忽视。

These results are only suggestive of the existence of a more general long-term relative age effect. Although the process that determines the relative age effect in sports is equivalent to that which determines the relative age effect in education, it is necessary to carry out further investigations in tertiary education system and in the more general labour market to gain generalisable conclusions on the existence of long-term relative age effects.

这一研究对更为一般的长期相对年龄效应仅供参考。即便相对年龄效应在运动项目中的机制与其在教育中的机制相同,想得到更为普适的结论,对高等教育和一般劳动力市场的研究仍是有必要的。

References

参考文献

[1] Bedard, K, E Dhuey (2006), "The Persistence of Early Childhood Maturity: International Evidence of Long-Run Age Effects", _The Quarterly Journal of Economics__ _121(4): 1437-1472.

[2] Black, S E, P J Devereux, K G Salvanes, (2011), "Too Young to Leave the Nest? The Effects of School Starting Age",_ _The Review of Economics and Statistics 93(2): 455-467.

[3] Böheim, E, M Lackner (2012), "Returns to Education in Professional Football", _Economics Letters__ _114(3): 326-328.

[4] Cascio, E U (2008), " Race to the Top? Relative Age and Student Achievement", VoxEU, 6 September,

[5] Crawford, C, L Dearden, E Greaves (2013), "The Impact of Age Within Academic Year on Adult Outcomes", Institute for Fiscal Studies, 1-46.

[6] Dixon, J, S Horton, P Weir (2011), "Relative Age Effects: Implications for Leadership Development", _International Journal of Sport and Society__ _2(2): 1-15.

[7] Dhuey, E, S Lipscomb (2009), "What makes a leader? Relative Age and High School Leadership",Economics of Education Review 27(2): 173-183.

[8] Du, Q, H Gao, M D Levi (2012), "The Relative-Age Effect and Career Success: Evidence from Corporate CEO",_ _Economics Letters 117(3): 660-662.

[9] Fumarco, L, G Rossi (2015), "Relative Age Effect on Labor Market Outcomes for High Skilled Workers – Evidence from Soccer", Working Papers in Management, Birkbeck, Department of Management, BWPMA, 1501, 1-50.

[10] Fumarco, L, G Rossi (2015), "Il titolare in squadra? Spesso è nato a gennaio", Lavoce, available at http://www.lavoce.info/archives/36467/il-titolare-in-squadra-spesso-e-nato-a-gennaio/.

[11] Hancock, D J, A L Adler, J Côté (2013), "A Proposed Theoretical Model to Explain Relative Age Effects in Sport", European journal of sport science 13(6): 630-637.

[12] Joyner, P W, W J Mallon, D T Kirkendall, W E Garret Jr. (2013), "Relative Age Effect: Beyond the Youth Phenomenon", T_he Duke Orthopaedic Journal__ _3(1): 74-79.

[13] Larsen, E R, I F Solli (2012), "Born to run Behind? Persisting Relative Age Effects on Earnings", University of Stravenger, Faculty of Social Sciences.

[14] Kniffin, K M, A S Hanks (2015), "Revisiting Gladwell's Hockey Players: Influence of Relative Age Effects upon Earning the PhD", Contemporary Economic Policy 34: 21-36.

[15] Matsubayashi, T, M Ueda (2015), "Relative Age in School and Suicide among Young Individuals in Japan: A Regression Discontinuity Approach", PLoS ONE 10(8): 1-10.

[16] Muller-Daumann, D, D Page (2016), "Political Selection and the Relative Age Effect in the US Congress", _Journal of Royal Statistical Society: Series A (_Statistics in Society) 1-21.

[17] Musch, J, R Hay (1999), "The Relative Age Effect in Soccer: Cross-Cultural Evidence for a Systematic Distribution against Children Born Late in the Competition Year", _Sociology of Sport Journal__ _16(1): 54-6.

Navarro, J-J, J García-Rubio, P R Olivares (2015), "The Relative Age Effect and Its Influence on Academic Performance",_ _PLoS ONE 10(10): 1-18.

[18] Peña, P A (2015), "Creating winners and losers: date of birth, relative age in school, and outcomes in childhood and adulthood", unpublished manuscript.

[19] Plug, E J S (2001), "Season of Birth, Schooling and Earnings", _Journal of Economic Psycholog_y 22(5): 641-660.

[20] Poli, R, L Ravenel, R Besson (2015), "Relative age effet: a serious problem in football", CIES Football Observatory Monthly Report 10.

[21] Ponzo, M, V Scoppa (2014), "The Long-Lasting Effects of School Entry Age: Evidence from Italian Students", Journal of Policy Modeling 36(3): 578-599.

[22] Roberts, S J, T Stott (2015), "A New Factor in UK Students' University Attainment: The Relative Age Effect Reversal?", _Quality Assurance in Education__ _23(3): 295 - 305.

[23] Thompson, A H, R H Barnsley, R J Dyck (1999), "A New Factor in Youth Suicide: The Relative Age Effect",_ _Canadian journal of psychiatry 44(1): 82-85.

[24] Zoëga, H, U A Valdimarsdóttir, S Hernández-Diaz (2012), "Age, Academic Performance, and Stimulant Prescribing for ADHD: A Nationwide Cohort Study", Pediatrics 130(6): 1012-1018.

Endnotes

尾注

1 This result has also been observed in other very competitive labour markets. Muller-Daumann and Page (2015) as well as Du et al. (2012) find evidence that people born toward the end of the selection year are under-represented among US congressmen and among CEOs for S&P 500 firms respectively. Finally, a similar result has been observed when investigating suicide rates in Japan and Canada. Matsubayashi and Ueda (2015) and Thompson et al. (1999) find that relatively younger people have a higher suicide rate.

该结果在其它竞争非常激烈的劳动力市场也被观察到。[Muller-Daumann and Page (2015)]以及[Du et al. (2012)]发现证据表明在选拔年度末尾出生的人在美国国会议员和标准普尔500强企业CEO中的比例低于应有比例。最后,相似的结果在对日本和加拿大自杀率的调查中也被观察到了。[Matsubayashi and Ueda (2015)]和[Thompson et al. (1999)]发现年龄相对小的人群有更高的自杀率。

2 To the best of our knowledge, before this study only Ashworth and Heyndels (2007) investigate the relative age effect on footballers' wages. They used a sample that covered a shorter period of time in the German first league from mid-1990s, and before the effects of the Bosman ruling fully kicked in (this ruling affected players' mobility and introduced free agency, possibly increasing competition among them).

就我们所知,在我们的研究之前只有[Thompson et al. (1999)]调查了相对年龄效应对足球运动员工资的影响。他们使用了来自德国一级联赛从1990年代中期开始的较短时期的样本,那时博斯曼法案的效果还未完全体现(博斯曼法案影响了运动员的流动性,引入了自由转会,因此可能加剧了运动员之间的竞争)。

翻译:约伯(@约伯_)

校对:混乱阈值(@混乱阈值)

编辑:辉格@whigzhou comments powered by Disqus