Head Space: Behind 10,000 Years of Artificial Cranial Modification

万年人工颅骨修饰下的头部空间

颅骨的刻意修饰,又称“图卢兹畸形”。(图片来源:Wikimedia Commons)

颅骨的刻意修饰,又称“图卢兹畸形”。(图片来源:Wikimedia Commons)

In 2013, archaeologists working in Alsace, in eastern France, uncovered something incongruous, and to the untrained eye, very strange. The researchers discovered the tomb and skull of an aristocrat, who died some 1,600 years ago. Her skull was heavily deformed, with the front flattened, and the rear rising into a cone shape. An amateur digger might have been forgiven for thinking they had found one of the “Grey aliens” that UFO-spotters regularly claim to see.

2013年,在法国东部阿尔萨斯(Alsace)工作的考古学家发现了一些突兀的东西,未受专业训练的人会觉得非常奇怪。研究人员发现了一位贵族的坟墓和头骨,该贵族死于约1600年前。她的头骨严重变形,额头扁平,而后脑勺隆起呈圆锥状。假如一位业余发掘者以为他们发现了UFO目击者常声称看到的“灰色外星人”,那也是情有可原的。

This was an example of “artificial cranial deformation,” or in layman’s terms, the practice of altering the head’s natural shape through force. As odd as it seems, this was not a singular incident, or only representative of fifth-century practices, or something that only happened in France. Until the early 1900s, a form of artificial cranial deformation was still taking place in Western France, in Deux-Sevres. Known as the Toulouse deformity, the practice of bandeau was common amongst the French peasantry. A baby’s head would be tightly bound and padded, to protect it from accidental impacts. At around the same time, the practice was still occurring in Russia and the Caucasus, as well as in Scandinavia.

这就是一例“人工颅骨修饰”,或用俗话说就是以外力改变头部自然形状的做法。尽管看起来诡异,但这并不是一次意外,也不是五世纪同类做法的唯一代表,甚至不是只出现在法国。直到二十世纪早期,法国西部的德塞夫勒省(Deux-Sevres)仍存在一种人工颅骨修饰的形式。名为图卢兹畸形的头部束带习俗在法国农民之中很常见。婴儿的头部会被紧紧束缚,并用衬垫保护头部不受意外冲击。大约在同时期,这种习俗也出现在俄国、高加索地区和斯堪的纳维亚。

It turns out that altering the shape of one’s head is not shockingly unique; it’s incredibly common, across time and geography. Its meaning isn’t fixed, so understanding why and how it happens can reveal much about the societies who choose to change the shape of their heads.

这说明改变头部形状的做法并没有那么令人震惊的独特;它在不同时间、不同地点都很常见。这种习俗的意义并不明确,所以理解这些社会选择改变头部形状的原因和方式,将会揭示出很多信息。

Originally, head flattening was instituted to “distinguish certain groups of people from others and to indicate the social status of individuals.” In Europe the practice was most popular with tribes that emigrated from the Caucasus region of Central Asia, like the Huns, Sarmatians, Avars, and the Alans. Indeed, that region is where the remains of the earliest suspected practitioners of artificial cranial deformation were discovered.

起初,头部扁平化是“为了将一群人同其他人区分开来,彰显个体的社会地位”。在欧洲,这些习俗流行于从中亚高加索地区移居来的部落,如匈人(Huns)、萨尔玛提亚人(Sarmatians)、阿瓦人(Avars)和阿兰人(Alans)。这些地方的确是发现最早疑似人工颅骨修饰者遗迹的区域。

While early European observers of the practice in France and in Eastern Europe reportedly pitied children whose heads had been bound, subsequent research has led experts to believe that cranial modification has no impact on cognitive function, nor is there a difference in cranial capacity. According to a 2007 paper in the journal Neurosurgery, “there does not seem to be any evidence of negative effect on the societies that have practiced even very severe forms of intentional cranial deformation.”

尽管早期观察到这种法国、东欧习俗的欧洲人会同情头部被束的儿童,但随后的研究让专家们相信,颅骨修饰对认知能力并没有影响,脑容量也并无不同。根据《神经外科》杂志上一篇2007年的文献,“即使在那些实行重度颅骨修饰的社会,也没有任何证据表明存在负面影响。”

(Photo: Didier Descouens/WikiCommons CC SA 3.0)

(Photo: Didier Descouens/WikiCommons CC SA 3.0)

In Iraqi Kurdistan, near the borders with Iran and Turkey, a cemetery from the proto-Neolithic period was discovered in 1960. The site, called Shanidar Cave, dates back more than ten thousand years, and contains the bodies of 35 individuals, including some of the first examples of intentional skull shaping. The Huns and Alans both seem to have originated in Central Asia, and as they pushed westward into the Roman Empire (often invited as mercenaries), their practice of head binding came with them, and was adopted by some peoples living in Western and Central Europe.

在伊拉克靠近伊朗和土耳其边境的库尔德斯坦地区,1960年发现了一座前陶器新石器时代的墓地。这个被称为“沙尼达尔洞穴(Shanidar Cave)”的地点有一万多年的历史,里面有35具尸体,包括一些最早实施人工颅骨修饰的人。匈人和阿兰人似乎都来源于中亚,随着他们向西推进到罗马帝国(常受邀充当雇佣兵),其束头习俗也随之传播,被一些住在中西欧的群体所接受。

The earliest written reference we have of artificial cranial deformation comes from Hesiod, a Greek poet who lived between 750 and 650 B.C. In his book of mythology, The Catalogues of Women, Hesiod referred to a tribe from either Africa or India called the “Makrokephaloi” (or “Macrocephali”), which roughly translates to “the big heads.”

我们拥有的关于人工颅骨修饰的最早文献来自生活于公元前750年到650年的希腊诗人赫西奥德。在他的神话《女性目录》中,赫西奥德提到了一个来自非洲或印度的部落,名为“Makrokephaloi”(或“Macrocephali”),大致可翻译为“大头族”。

Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, also mentions the Macrocephali in his work, On Airs, Waters, and Places, which was written around 400 B.C. Not only did Hippocrates mention the Macrocephali, but he got their techniques right. Rather than making the people mythological, Hippocrates tells us their methods, and their reasons: “They think those the most noble who have the longest heads … after the child is born, and while its head is still tender, they fashion it with their hands, and constrain it to assume a lengthened shape by applying bandages and other suitable contrivances …”

西方医学之父希波克拉底也曾在作品《空气、水和地方》中提到Macrocephali,该书写于约公元前400年。希波克拉底不只提到过Macrocephali,而且还弄清了相关技术。希波克拉底没有将这些人神化,而是告诉我们他们束头的方法和原因:“他们认为越尊贵的人头越长……在婴儿出生后,当婴儿头部还很软时,他们就动手改变头部形状,用绷带和其他适合的工具束缚头部来呈现拉长的形状……”

And it is not only European authors who found the practice amazing. Xuanzang, a Chinese Buddhist monk and traveller, whose 17-year journey to India inspired the Chinese classical novel Journey to the West, reported on the form of the practice he came across in modern-day Xinjiang, in Western China. Xuanzang speaks of the people of Kashgar, where “children born of common parents have their heads flattened by the pressure of wooden boards …”

并不是只有欧洲作者惊奇于此种习俗。中国佛教僧人和旅行者玄奘的17年印度之旅为中国经典小说《西游记》提供了灵感,他也曾报道过这种习俗,是在当今中国西部新疆地区碰到的。玄奘提到了喀什葛尔(Kashgar)的人们,那里普通人家的孩子头部会被用木板压平。

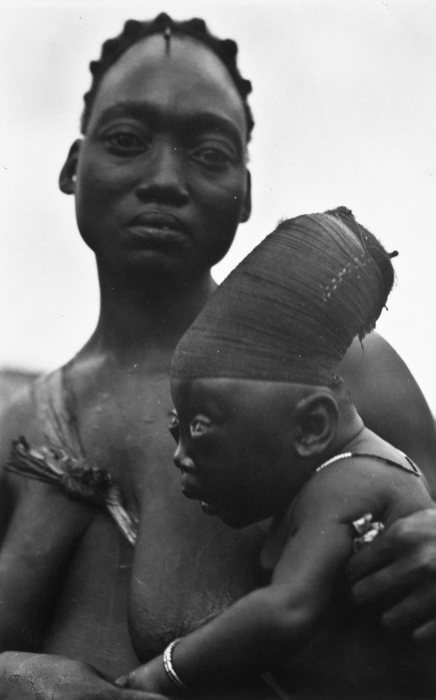

(Photo: Tropenmuseum/ Royal Tropical Institute/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

(Photo: Tropenmuseum/ Royal Tropical Institute/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Thus, this woman discovered in France fits into a broader cultural narrative—one of migration, of high rank and social status, and of conquest. While it would be easy to write the practice off as being an odd thing that was popular thousands of years ago, it wouldn’t be anywhere near the truth.

因此,在法国发现的这个女人可以被装进更宏大的文化叙事——有关迁移,有关高等级和高地位,有关征服的故事。尽管将这种习俗贬为几千年前流行的诡异事情是很方便的,但这并不能让我们接近真相。

Across the Americas, in various tribes, infants had their heads bound and shaped by their parents. Both the Mayans and the Inca shaped their children’s skulls, as did the Choctaw and the Chinookan tribes in what is now the United States. Their reasons must have been the same, to allow for the child to fit into the fabric of their societies, and to signify class. For the Maya, it also held a religious significance.

在美洲一些部落中,父母也会束缚婴儿的头部来改变其形状。玛雅人和印加人都会改变儿童的颅骨形状,正如当今美国的巧克陶和奇努克部落。他们这么做的理由一定是相同的,就是让孩子融入他们的社会结构,并跻身于显贵等级。对玛雅人来说,这还有宗教意义。

According to Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, a Spanish chronicler of the conquest of the Americas, a Mayan explained: “This is done because our ancestors were told by the gods that if our heads were thus formed we should appear noble …”

根据西班牙征服美洲编年史作者Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo,一名玛雅人如此解释道:“这么做是因为我们祖先被神告知,如果我们头部被如此改造成型,我们就会显得高贵……”

Two different styles of artificial cranial deformation were prevalent in Mayan culture, and indicated the wearer’s rank. Those who were destined (or hoped) to hold some position of high status, were given what is referred to as “oblique deformations,” which resulted in a high, pointed head shape. However, the general populace could only use an “erect deformation,” which led to a rounded skull shape, with flattening on the sides. Whether these shapes were in imitation of a jaguar’s skull, to show prowess, or in the shape of the maize god, to symbolise fertility, is a matter of debate among historians and archaeologists.

两种不同类型的人工颅骨变形在玛雅文化中流行,而且显示了所有者的等级。那些注定(或希望)拥有高等社会地位的人会施行“斜角变形”,形成又高又尖的头部形状。然而,一般人只能使用“垂直变形”,形成颅骨浑圆、两侧扁平的形状。这些头部形状究竟是模仿美洲虎的颅骨来显示力量,还是模仿玉米神来象征丰收,历史学家和考古学家还在争论不休。

秘鲁伊卡城中伊卡地区博物馆展示的帕拉斯卡头骨(图片来源:Wikimedia Commons)

秘鲁伊卡城中伊卡地区博物馆展示的帕拉斯卡头骨(图片来源:Wikimedia Commons)

Artificial cranial deformation was also recorded amongst the remains of people as far distant as Australia and the Caribbean islands. But it’s not just an ancient practice. It still occurs in some of the world’s more remote outposts.

人工颅骨修饰也记录在远至澳大利亚和加勒比诸岛的人类遗迹之中。但这不只是一种古代风俗。它仍然存在于世界上一些更偏远的村落。

In Polynesia, the tradition still (rarely) occurs, as it does in the people of Mangbetu tribe, of Congo. In Vanuatu, the shape is associated with famous folk heroes and religion. A person from Malekula, an island in the Vanuatu chain, told the veteran anthropologist Kirk Huffman: “it originates with the basic spiritual beliefs of our people. We see that those with elongated heads are more handsome or beautiful, and such long heads also indicate wisdom.”

在波利尼西亚,这种传统仍然存在(虽然已很罕见),刚果芒贝图部落族人就是如此。在瓦努阿图,头部形状是与著名的民族英雄和宗教相联系的。一位来自马拉库拉岛——位于马努阿图岛链——的人曾对经验丰富的人类学家柯克·霍夫曼说:“这种习俗源于我们人民基本的精神信仰。我们认为那些拥有拉长头部的人更加英俊或漂亮,而且这种长脑袋也表示有智慧。”

More than a millennia after she died, the ancient aristocratic woman discovered in Alsace isn’t alone. Like any body modification, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. She still has people whose cultures revere the same head-shape and customs as her own.

在死后一千多年里,这位在阿尔萨斯发现的古代贵妇并不孤独。像任何人体修饰一样,美不美只能由观者说了算。而如今,她仍然拥有像她一样崇敬同样头型和习俗的同好。

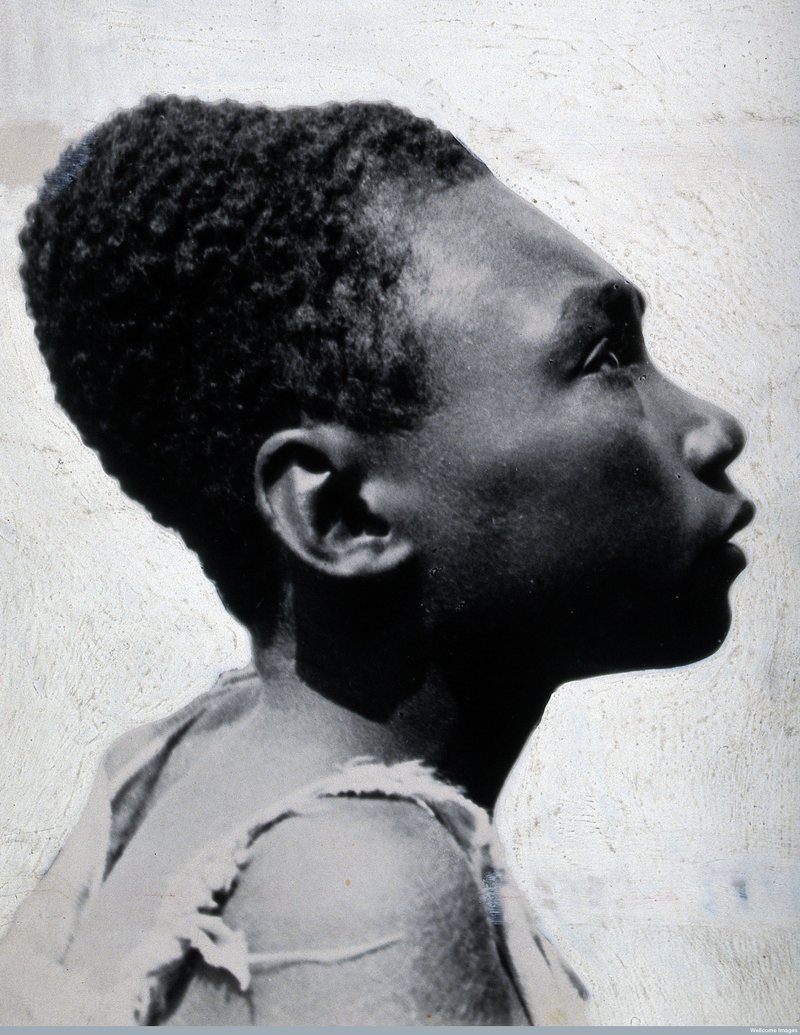

(Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

(Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

翻译:尼克基得慢

校对:babyface_claire(@许你疯不许你傻)

编辑:辉格@whigzhou comments powered by Disqus