The Valorization of Envy

赋予嫉妒以价值

Robert Nozick, among others, wondered to what degree left-wing conceptions of social justice are mere attempts to valorize envy. (Extreme left-wing views in the US, in particular, tend to concentrated among privileged upper-middle class liberal arts grads in the 2% who are angry with the 1%.) As an example of an envious rant, check out this remarkable essay at Counterpunch, “The Economic Inequality of Academia”., by Richard Goldin. An excerpt:

罗伯特·诺齐克,还有其他一些人,都曾想知道,左翼的社会正义概念在多大程度上仅仅是尝试给嫉妒定价。(尤其是美国的极左翼观念,其往往集中出现在来自优越的中产阶级上层、身处收入顶层2%的文科毕业生中,他们对那1%愤怒有加。)嫉妒的咆哮之例证,请看网站Counterpunch的这篇神奇文章:“学术界的经济不平等”,文章作者是Richard Goldin。以下是两段摘录:

Paths to knowledge are often forged through the interplay of publications and teaching. No objective standard of measurement exists to financially quantify, and differentiate, these approaches or their contributions. Yet a vast and enduring economic hierarchy has emerged grounded in the supposed intrinsic hierarchy between the two. This financial hierarchy is not a dispassionate reflection of an objective reality; it is a strategic effect of the mechanisms underlying class formation and preservation.

“通往知识的道路通常都由出版和教学的相互作用而铺成。世上并不存在什么客观的测量标准,能为这两种方法或它们的贡献做财务上的量化和区分。但是,在两者之间被公众认受的内在等级区分之上,产生出了一个庞大且持久存在的经济等级制度。这种财务等级制度不是对客观现实的一种公正反映,它是塑造和维护阶层的社会机制的策略效应。”

The primacy of publishing, and the attendant allocation of resources, is utilized not merely to perpetuate two different economic classes, but also to create two different kinds of people. This creation allows the hierarchy of privilege to function as though it represents objective value differences both in terms of the work produced and the individuals who produce it.

“出版第一及伴随而来的资源分配,不仅仅被用来维持两个不同的经济阶层,而且被用来创造不同的两个人群。这种创造令特权等级制的运转好像是体现了一种客观的价值差异,当中既包括劳动成果之间的价值差异,也包括提供劳动的个体之间的价值差异。”

Some comments on the essay:

对此文我有几点评论:

1.Like many essays in this genre, it has its facts wrong. It claims that the majority of faculty are adjuncts, but that is just false. As Phil Magness documents here, at normal four-year, not-for-profit universities and colleges, the majority of faculty are tenure-track. Even when we include for-profit and community colleges, which rely disproportionately on adjunct labor, the majority of faculty in the US are not adjuncts. (See this post, too.)

1.跟诸多此类文章一样,这篇文章也有事实错误。它声称教员中多数都是兼职人员,这绝对是错的。Phil Magness已证明,在一般的四年制非营利性大学和学院中,多数教员是终身轨。即使将极为依赖兼职劳动力的营利性院校和社区学院都包括进来,美国的大学教员中多数也不是兼职。

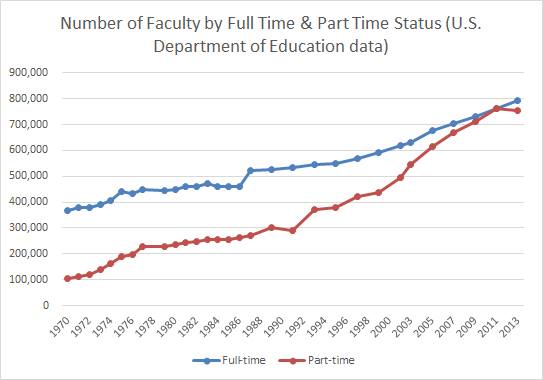

Also, contrary to what everyone keeps saying, the number of tenure-track faculty slots has been increasing over the past 40 years. Here’s a chart with US Dept of Ed data, again from Magness:

并且,跟大家历来的说法相反,终身轨教职【译注:终身轨,美国大学一种教职序列,只有进入终身轨的教员方有可能转正为终身教授,因此又称预备终身】空缺数过去40年间一直在增加。下图还是来自Magness,数据采自联邦教育部:

It’s bizarre that the madjunct crowd keeps repeating obviously false claims, such as that they make minimum wage. Can’t they make their point without lying? I suspect the issue here is that many of these people are postmodernists, and for postmodernists, the concepts of “truth” or “facts” are just attempts to wield power over others. Or perhaps Dr. Goldin is being funded by the Koch brothers as part of a neoliberal assault to undermine the credibility of academia.

It’s bizarre that the madjunct crowd keeps repeating obviously false claims, such as that they make minimum wage. Can’t they make their point without lying? I suspect the issue here is that many of these people are postmodernists, and for postmodernists, the concepts of “truth” or “facts” are just attempts to wield power over others. Or perhaps Dr. Goldin is being funded by the Koch brothers as part of a neoliberal assault to undermine the credibility of academia.

“疯狂兼职人”群体总是在重复明显错误的主张,比如声称自己赚的是最低工资。这真是奇特。他们在立论时就不能不撒谎吗?我怀疑此处的问题是,这些人中有许多都是后现代主义者,而对于后现代主义者,“真理”或“事实”这种概念都只是对他人行使权力的企图。或者,也许Goldin博士是得了科赫兄弟【译注:美国富豪,积极参与政治,资助传统基金会和加图研究所等保守派和自由意志主义智库,常被左派攻击为右派幕后黑手】的资助,正为一场旨在摧毁学术界公信力的新自由主义攻势出力。

2.The essay claims that the academic 1% do as well as they do because the burdens of teaching are shifted onto poorly paid adjuncts. But the rather obvious problem with this claim is that the places where the academic 1% reside are not the places that use lots of adjuncts. The top researchers end up in places like Princeton, Harvard, MIT, and Penn. These schools do not make heavy use of adjunct faculty. (Insofar as they do use them, many of their adjuncts are professionals with full-time jobs, who teach extra clinical classes in their law and business schools.) For Goldin’s argument to succeed, he’d have to show us that the reason the academic 1% do so well is because their employers somehow exploit the adjuncts working at other universities and colleges.

2.文章声称学术界的1%们之所以能有今天这样的表现,是因为教学负担被转移到了收入平平的兼职教员头上。但是这一断言的一个特别明显的问题是,学术界那1%所在的地方,就不是大量使用兼职人员的地方。顶级的研究人员都流向了如普林斯顿、哈佛、麻省理工、宾大等地方,而这些学校并没有大量使用兼职教员。(即使确实为它们所用的兼职人员,其中也有许多是拥有全职工作的专业人士,他们只在法学院和商学院里额外讲授实操课程。)Goldin的论证要成立,他就必须向我们证明,学术界的1%之所以能有今天的优异表现,是因为他们的雇主以某种方式剥削了其他大学和学院里的兼职工作人员。

I’m an academic 1-percenter, but it’s not because adjuncts do all my teaching for me. We do have a two-tier system, it’s true. In our system, the majority of faculty are extremely well paid tenure-track professors with high research expectations and low teaching loads; the minority are very well paid permanent teaching faculty with higher teaching loads. (According to this website, Goldin makes $30.5K a year, which is only a tiny fraction of what we pay our non-tenure track teaching faculty. Indeed, we pay our non-tenure-track faculty better than Cal State Long Beach pays their tenure-track faculty.) We use few adjuncts.

我就是学术界1%中的一个,但这不是因为兼职教员承担了我所有的教学事务。我们这里确实有一个双轨制,这是真的。在我们的这一制度下,教员的多数都是终身轨教授,报酬非常高,研究前景非常好,教学任务很轻;少数人则是长期职位(permanent)的教学教员,报酬很高,教学任务较重。(根据这个网站,Goldin每年能赚3.5万美元,只是我们这里的非终身轨教学教员报酬的一个零头。事实上,我们付给非终身轨教员的报酬比加州州立长滩分校【译注:即吐槽对象Richard Goldin任职的学校】付给其终身轨教员的还要高。)我们极少使用兼职教员。

I’m not making bank because Georgetown exploits adjuncts. Martin Gilens isn’t making bank because Princeton exploits adjuncts. R. Edward Freeman doesn’t make bank because Darden exploits adjuncts. Rather, the exploited adjuncts are getting exploited elsewhere, at community colleges, small liberal arts colleges, third tier/low output “research” universities, and the for-profit colleges.

我不是因为乔治敦大学剥削兼职教员而发财。Martin Gilens不是因为普林斯顿大学剥削兼职教员而发财。R. Edward Freeman不是因为达顿商学院剥削兼职教员而发财。其实,被剥削的兼职教员是在别的地方被剥削的,比如社区学院、小型的文理学院、第三档或者低产出的“研究型”大学以及营利性学院。

3.Goldin has some interesting points about whether research is overvalued and teaching undervalued. But we should keep in mind the economics of the situation. Good teachers are a dime a dozen. It’s easy to find people who can teach low-level undergraduate courses well. It’s easy to teach these classes well, and many people can do it. The supply of good teachers is very high. But good researchers are rare. Most faculty cannot consistently publish in high-level venues. The supply of good researchers is low. (It’s easy to publish in obscure third and four-tier journals and presses, but difficult to publish in prestigious top-tier journals and presses.) Even if universities valued teaching and research equally, we’d expect the star researchers to be paid more than the star teachers, because star teachers are easy to come by.

3.关于研究是否估值过高而教学是否估值过低,Goldin提出了一些有趣的论点。但我们要牢记这种情形里的经济学道理。好的教师四处都有,我们很容易找到能把低水平的本科课程讲得很好的教师。这些课也容易教得好,很多人都可以做到。优秀教师的供给是很充足的。但优秀研究者则很少见。多数教员不能稳定地在高水平场合发表成果。优秀研究员的供给是不足的。(在不知名的三、四流杂志或出版社发表成果很容易,但在极富盛名的一流杂志和出版社就难了。)即使大学同等重视教学和研究,我们也会预期明星研究员所得的报酬比明星教师要多,因为明星教师得之不难。

I realize that as a Counterpunch author, it’s unlikely Goldin has ever seen an economics textbook. But I’d invite him to go to Cal State Long Beach’s library, check out Mankiw’s undergrad econ textbook, turn to pages 6-7, and read about the diamond-water paradox.

Goldin是Counterpunch网站的作者,我估计他很可能从未看过任何经济学教材。但我很乐意邀请他去趟加州州立长滩分校的图书馆,借本曼昆的经济学本科教材,翻到第6-7页,读读钻石和水的悖论【译注:即价值悖论,水对人的生存极为重要,但市场价值远比无甚大用的钻石低】。

4.Consider this quotation:

4.思考一下文中这样一段话:

It is teachers dedicated to a challenging education who engage in the task of reworking and concretizing theories to make them relevant to students. It is in the classroom where the dialogue between theory and politics takes place; and it is the classroom which sends forth generations of students who can perceive, and possibly undermine, the rationalities of power.

“从事理论修订和具体化这一任务,使之能被学生理解的,是那些献身于具挑战性的教育事业的教师;理论与政治之间的对话,是在课堂上进行的;一代又一代能够理解权力合理性,并且可能还会将之摧毁的学生,也是从课堂上走出来的。”

Paths to knowledge are often forged through the interplay of publications and teaching.

“通往知识的道路通常都由成果发表和教学的相互作用而铺成。”

What should we make of this? Is coming up with general relativity less of an achievement than teaching it to undergrads secondhand? Is writing A Theory of Justice less of an achievement than teaching it to undergrads secondhand? Is writing the stuff that gets into the textbooks less of an achievement than teaching the textbook to undergrads?

我们该怎么去理解这段话?提出广义相对论的成就不如把它二手教给本科生?写出《正义论》的成就不如把它二手教给本科生?写出那些进入了教科书的东西,其成就不如向本科生讲授教科书?

Also, after reading Academically Adrift, it’s not clear to me that college teaching is undervalued. It might instead be overvalued.

而且,在读了《学术漂泊》以后,我都不太确定大学教学是否确实被低估了。它甚至有可能被高估了。

5.Goldin, like many writing in this genre, claims that academia is a lottery. This view is problematic. First, if it were a lottery, we’d expect that the type of people being hired as tenure-track at Harvard would have average credentials, but, on the contrary, the top schools tend to hire people with the best publication records. Second, the way the madjunct crowd reacts to their failure to secure good jobs doesn’t match how people react when they lose lotteries. My Uncle Freddy like to play the lottery from time to time. When he lost, he didn’t act surprised, claim that the system is unfair, and demand redistribution from the winners to the losers. Rather, he expected to lose, threw out his losing tickets, and kept living his life. If madjunct crowd sincerely believed that academia is a lottery, they would not act surprised or indignant that they lost and would move on with their lives.

5.跟许多写作此类文章的人一样,Goldin宣称学术界就是大抽奖。这种观点是有问题的。首先,如果确实是抽奖,我们就可以预期哈佛所聘用的终身轨人员将会是些成就处于平均水平的人,但是正好相反,顶尖学校都更倾向于聘用著述丰厚的人。第二,“疯狂兼职人”群体在没能保住自己的好工作时,其反应与人们抽奖落空后的反应并不相同。我的叔叔Freddy时不时就去抽奖。抽不中他也不觉得稀奇,不会说这个制度不公平,也不会要求中了奖的人把奖品拿出来和抽不中的瓜分,他只会丢了没中奖的彩票,生活照旧。如果“疯狂兼职人”群体真心觉得学术界就是抽奖,那他们就不会为自己的失败而感到惊讶或愤怒,只会继续自己的生活。

翻译:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:小册子(@昵称被抢的小册子)

编辑:辉格@whigzhou