Learning unleashed

挣脱枷锁的教育

Where governments are failing to provide youngsters with a decent education, the private sector is stepping in

在政府不能为青少年提供像样教育的地方,私人力量正着手发挥作用。

THE Ken Ade Private School is not much to look at. Its classrooms are corrugated tin shacks scattered through the stinking streets of Makoko, Lagos’s best-known slum, two grades to a room. The windows are glassless; the light sockets without bulbs. The ceiling fans are still.

Ken Ade私立学校并不起眼,他们的教室是波纹铁皮窝棚,分布在拉各斯最为知名的贫民窟Makoko的发臭街道上,一个教室里有两个年级。窗户上没有玻璃,灯座上没有灯泡,吊扇也不转动。

But by mid-morning deafening chants rise above the mess, as teachers lead gingham-clad pupils in educational games and dance. Chalk-boards spell out the A-B-Cs for the day. A smart, two-storey government school looms over its ramshackle private neighbour. Its children sit twiddling their thumbs. The teachers have not shown up.

但每到上午,这堆烂摊子里会传来震耳欲聋的声音,因为老师们会带着那些穿着方格花布衣服的学生进行有教育意义的游戏和舞蹈。教室的黑板上会写明当日的功课。一个整洁的两层公立学校就矗立在这家摇摇欲坠的私立学校旁边。公立学校的孩子在那坐着摆弄他们的手指,老师并没有出现。

Recent estimates put the number of low-cost private schools in Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital, as high as 18,000. Hundreds more open each year. Fees average around 7,000 naira ($35) per term, and can be as low as 3,000 naira. By comparison, in 2010-11 the city had just 1,600 government schools. Some districts, including the “floating” half of Makoko, where wooden shacks stand on stilts above the water, contain not a single one.

最近的调查估计,尼日利亚商业之都拉各斯有将近1.8万所低成本的私立学校,而且每年会新增几百所。学费平均为每学期7000奈拉(约合35美元),有时甚至低至3000 奈拉。与此形成鲜明对比的是,在2010-11年,这个城市只有1600所公立学校。在有些地区,包括 Makoko 的“漂浮区”——搭在水中立柱之上的木棚子——一所公立学校也没有。

In the developed world private schools charge high fees and teach the elite. But Ken Ade is more typical of the sector, not just in Nigeria but worldwide. In 2010 there were an estimated 1m private schools in the developing world. Some are run by charities and churches, or rely on state subsidies. But the fastest-growing group are small low-cost schools, run by entrepreneurs in poor areas, that cater to those living on less than $2 a day.

在发达国家,私立学校会收取高昂的学费,并且学生多为精英。但是Ken Ade在私立学校中更为典型,不仅在尼日利亚是这样,在全世界范围内都是如此。据估计,2010年发展中国家有大约一百万所私立学校,其中有些由慈善机构和教会运营,或者依靠国家补贴。但增长最快的部分,是由贫困地区的企业家经营的低成本小型学校,服务于那些每日生活费低于两美元的人。

Private schools enroll a much bigger share of primary-school pupils in poor countries than in rich ones: a fifth, according to data compiled from official sources, up from a tenth two decades ago (see chart 1). Since they are often unregistered, this is sure to be an underestimate.

私立学校在贫穷国家招收到小学生(占学生总数)的比重远高于富裕国家的相应比例:根据官方统计数据,这一数字为五分之一,20年前为二十分之一(见图一)。由于很多私立学校并未登记注册,所以这一数据存在低估。

A school census in Lagos in 2010-11, for example, found four times as many private schools as in government records. UNESCO, the UN agency responsible for education, estimates that half of all spending on education in poor countries comes out of parents’ pockets (see chart 2). In rich countries the share is much lower.

例如,2010-11年拉各斯的一项学校普查表明,实际存在的私立学校数量是政府登记数量的四倍。负责教育的联合国机构UNESCO估计,在贫穷国家,全部教育经费中有一半由孩子的父母承担(见图二)。而在富裕国家,这一比率要低很多。

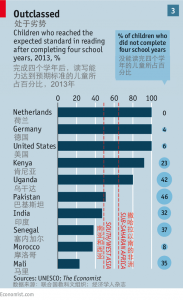

One reason for the developing world’s boom in private education is that aspirational parents are increasingly seeking alternatives to dismal state schools. In south and west Asian countries half of children who have finished four years of school cannot read at the minimum expected standard (see chart 3). In Africa the share is a third.

私立教育在发展中国家迅速兴起的一个原因是很多父母望子成龙,越来越多地在无能的公立学校之外寻找替代选择。在南亚和西亚国家,半数上了四年学的学生阅读能力达不到最低的预期标准(见图3)。在非洲这一比率为三分之一。

In 2012 Kaushik Basu, now at the World Bank but then an adviser to India’s government, argued that India’s rapidly rising literacy rate was mostly propelled by parents spending on education to help their children get ahead. “Ordinary people realised that, in a more globalised economy, they could gain quickly if they were better educated,” he said.

2012年,当时身为印度政府顾问的Kaushik Basu(现供职于世界银行)认为,印度的识字率迅速上升得益于印度父母为帮助孩子取得成功而在教育上花费的投入。他说:“普通民众意识到,在一个更加全球化的经济环境下,得到更好的教育赚钱就会更快”。

Many poor countries have failed to build enough schools or train enough teachers to keep up with the growth in their populations. Half have more than 50 school-age children per qualified teacher. And though quite a few dedicate a big share of their government budgets to education, this is from a low tax base.

许多贫穷国家没能建立起足够多的学校或者培养出足够多的老师,以跟上其人口增长。其中的半数国家中,每位合格教师需要带超过50个学龄儿童。尽管有少数国家在教育方面投入了很大部分的政府预算,但其税收基础本来就不高。

Some money is siphoned off in scams such as salaries for teachers who have moved or died, or funding for non-existent schools. Since 2009 Sierra Leone has struck 6,000 fake teachers off its payroll by checking identities before paying salaries. A national survey in Pakistan recently found that over 8,000 state schools did not actually exist.

有些钱还被骗走了,比如发放给了离职或已过世的教师当薪水,或者对一些根本不存在的学校提供资金支持。从2009年至今,通过发薪前的身份核查,塞拉利昂已经从其工资名册上砍掉了600名假老师。巴基斯坦的一项全国调查最近发现,有8000多所公立学校实际上根本不存在。

State schools are often plagued by teacher strikes and absenteeism. In a slum in eastern Delhi where migrants from north-east India cluster, pupils split their days between lessons in small private schools in abandoned warehouses that charge 80-150 rupees ($1.25-2.35) a month, and a free government school around the corner, which supplies cooked midday meals and a few books, but little teaching. When researchers visited rural schools in India in 2010 they found that a quarter of teachers were absent.

教师罢工和缺勤经常困扰着公立学校。在德里东部有一个由来自印度东北部的移民聚居的贫民窟,学生们在一个小型私立学校与一个免费公立学校之间穿梭。私立学校建在一个废弃工厂里,每月学费是80-150卢比(约合1.25-2.35美元);而公立学校就在附近拐角处,提供午饭和一些书,但几乎没什么教学。2010年当调查人员访问印度乡村学校时,发现有四分之一的教师缺勤。

A study by the World Bank found that teachers in state-run primary schools in some African countries were absent 15-25% of the time. “The public teachers don’t feel obligated coming to school,” says Emmanuel Essien, a driver who hustles day and night to send his youngsters to a private school in Alimosho, a suburb of Lagos. “If they come, they might just tell the student to go hawking. They tell you that your children have to attend an extra class, or buy an extra book, just so they can make money in their own pocket.”

世界银行的一项研究发现,非洲一些国家的公立小学教师有15-25%的时间缺勤。Emmanuel Essien是一名司机,他日夜奔忙、拼命赚钱来把他的孩子送到位于拉各斯郊区Alimosho的一所私立学校,他说,“公立学校的教师对于去学校并没有很强的责任感。如果他们去了,或许会让学生出去兜售东西。他们会说你的孩子必须参加额外的补习,或者额外买一些书,只是为了从你身上赚更多的钱。”

Privatising Parnassus

教育私有化

Given the choice between a free state school where little teaching happens and a private school where their children might actually learn something, parents who can scrape together the fees will plump for the latter. In a properly functioning market, the need to attract their custom would unleash competition and over time improve quality for all.

公立学校免费但几乎学不到东西,而在私立学校上学的孩子或许可以真真正正地学到一些东西,当面临这两种选择时,那些能凑够学费的家长会坚决选择后者。在一个运转正常的市场里,为了吸引顾客,会引起竞争,随着时间推移可以提高所有服务者的质量。

But as a paper by Tahir Andrabi, Jishnu Das and Asim Ijaz Khwaja published by the World Bank explains, market failures can stop that happening. Choosing a private school can be a perfectly rational personal choice, but have only a limited effect on overall results.

但世界银行发表的一篇由Tahir Andrabi, Jishnu Das 和Asim Ijaz Khwaja三人撰写的论文显示,市场失灵会阻止上述情况的发生。选择私立学校对于个人来说也许是完全理性的选择,但对于整体来说只有很有限的影响。

One such failure is that parents often lack objective information about standards. Countries where state schools are weak rarely have trustworthy national exam systems. To attract clients, private schools may exaggerate their performance by marking generously. Mr Essien says he has taken to testing his children himself to cross-check their progress. Though paying customers like him can hold private-school teachers to account, making them more likely to turn up and try hard, good teachers cannot be conjured out of thin air.

其中的一个失灵是,父母通常缺乏关于评价标准的客观信息。公立学校较弱的国家很少有值得信任的国家考试系统。为了吸引到学生,私立学校也许会通过宽松评分的方式来夸大学生的成绩。Essien说他已经开始自己动手测试他的孩子,以便对学习成效进行交叉评测。尽管像他这样的付费家长可以促使私立学校的老师承担责任,让他们更有可能勤快并努力地教学,但好老师不是凭空就能变出来的。

Matters are further complicated by the fact that education is to a great extent a “positional good”: the aim is to get a job or university place, for which it is enough to beat the other candidates, rather than reach the highest possible absolute standard. Especially in rural areas where there is unlikely to be much choice, being just a bit better than public schools is enough to keep the clients coming, says Joanna Harma of the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex. And sheltered from market forces, those public schools have no incentive to improve.

实际上问题要更复杂一点,因为教育在很大程度上是一种“排位商品”:它的目的是找到一份工作或者考上一所大学,因此只要能击败其他候选人就足够了,而不是去达到可能的最高绝对标准。特别是在乡村地区,那里没有更多的选择,只要比公立学校好一点就足够吸引到学生了,Sussex大学国际教育中心的Joanna Harma说道。由于避开了市场的力量,这些公立学校没有动力去提高自身的教学水平。

That means school choice can “sort” children into different types of schools: the most informed and committed parents colonise the better ones, which may then rely on their reputations to keep their position in the pecking order.

这意味着择校过程会把学生“分到”不同的学校中去,那些消息最灵通和最负责任的家长蜂集于好学校,然后这些学校就可以依靠它们的名声来保持其在等级排序中的位置。

Research from several parts of Africa and south Asia finds that children in low-cost private schools are from families that are better-off, get more help from parents with homework and have spent more time in pre-school.

非洲和南亚的一些研究发现,低成本私立学校的学生多来自富裕家庭,他们在家庭作业上能得到父母更多的帮助,并在学前教育方面花费了更多时间。

A round-up of research, much of it from south Asia, found that their pupils did better in assessments, though often only in some subjects. In the few studies that accounted for differences in family background and so on, their lead shrank.

一项主要在南亚进行的汇总研究显示,那里的学生在考核中成绩更好,尽管通常只是在几个学科。在少量将家庭背景差异等因素考虑进去的研究中,这种优势就缩小了。

Chile’s voucher scheme, which started in 1981 under the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, aimed to enable poor students to move from bad public schools to good private ones and to raise standards by generating competition between the two. Today 38% of pupils are in state schools, 53% in private ones that accept vouchers and 7% in elite institutions that charge full fees. In the 1990s a post-Pinochet centre-left government allowed subsidised schools to charge top-up fees. They can also select their pupils by ability.

智利的教育券计划,开始于1981年奥古斯托·皮诺切特将军独裁时期,目的是让贫穷的孩子有机会从差劲的公立学校转移到好一点的私立学校,并通过两者间的竞争来提高标准。现在38%的孩子在公立学校,53%的孩子在可以用教育券的私立学校,7%在收取全额费用的精英机构。在1990年代,后皮诺切特的中左派政府允许受补贴的学校收取“补充”学费。他们还可以根据能力来选择学生。

Chile does better than any other Latin American country in PISA, an international assessment of 15-year-olds in literacy, mathematics and science, suggesting a positive overall effect. But that is hardly a ringing endorsement: all the region’s countries come in the bottom third globally.

智利在PISA中比其他拉美国家做得都好,PISA是一份针对15岁学生的读写、数学和科学能力的国际评估,这显示智利政策整体效果积极。但这并非什么强有力的证据,因为这一地区的国家排名都在全球的倒数第三位。

And once the relatively privileged background of private-school pupils is taken into account, says Emiliana Vegas of the Inter-American Development Bank, state schools do better, especially since they serve the hardest-to-teach children.

美洲开发银行的 Emiliana Vegas说,一旦把私立学校学生相对优越的家庭背景考虑在内,公立学校做得更好,特别还要考虑到,他们教的是最难教的学生。

Where private schools trounce state ones is in cost-effectiveness. A recent study in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh gave vouchers for low-cost private schools to around 6,000 randomly chosen pupils. Four years later they were compared with applicants who did not receive the vouchers. Both groups did equally well in mathematics and Telugu, the local language. But private schools had spent less time on these subjects in order to make space in the curriculum for English and Hindi, in which their pupils did better. And spending on each pupil was only around a third that in the state sector. Lagos state spent at least $230 on each child it put through primary school between 2011 and 2013, public data suggest, around twice as much as a typical private school charges.

私立学校稳胜于公立学校的地方是在成本效益方面。在印度安得拉邦进行的一项调查,给随机挑选的约6000学生发放了可用于低成本私立学校的教育券。四年之后,把他们和没拿到教育券的学生进行对比。两组人在数学和Telugu(一种当地语言)上表现得一样好。但是私立学校的学生在这些学科上花费的时间更少,以便腾出时间来学习英语和印地语,在这两个学科上私立学校的学生做的更好。每个孩子的培养费用仅为公立学校的三分之一。公开数据显示,在2011至2013年间,(尼日利亚)拉各斯州在每个完成小学学业的孩子身上花费了约230美元,大约是一个典型的私立学校索费的两倍。

Marks for effort

努力的成绩

A centre-left government in Chile is now unwinding Pinochet’s reforms. One of its changes is to bar for-profit schools from the voucher scheme. The new standard-bearer for market-based education reform is the Pakistani province of Punjab. Nationally, 25m children are out of school, and reformist politicians are turning to the private sector to expand capacity quickly and cheaply. To make the market work better, they are exploring ways to give parents more information about standards and to help successful schools grow.

智利现有的中左政府正在颠覆皮诺切特改革,其举措之一是将盈利性学校踢出教育券计划。于是,这场教育市场化改革中的旗手角色,已让位于巴基斯坦的旁遮普省。巴基斯坦全国共有2500万名失学儿童,改革派政治家把目光投向私人部门,以期快速而廉价地扩大教育容量。为帮助市场更好运行,他们正采取措施,给予学生家长更多学业水平的相关信息,并帮助已获成功的学校良好发展。

Authority over education is devolved to Pakistan’s four provinces, and Punjab’s energetic chief minister, Shahbaz Sharif, the brother of the prime minister, Nawaz, has decreed that the government will not build any of the new schools needed to achieve its 100% enrolment target for school-age children by 2018. Instead money is being funnelled to the private sector via the Punjab Education Foundation (PEF), an independent body with a focus on extremely poor families.

巴基斯坦已将教育事务的管理权下放给四省的地方政府。精力旺盛的旁遮普省首席部长,总理纳瓦兹·谢里夫的弟弟沙巴兹·谢里夫宣布,实现2018年前学龄儿童100%入学目标所需的学校,政府一座都不会修建。相反,借由关注极端贫困家庭的独立组织旁遮普教育基金会(PEF),资金会被输送至私人部门。

One scheme helps entrepreneurs set up new schools, particularly in rural areas. Another gives vouchers to parents living in slums to send children who are not in school to PEF-approved institutions. All the places in some schools have also been bought up. Those schools cannot charge fees and must submit to monitoring and teacher training.

其中一项计划旨在帮助企业家开办新学校,特别是在乡村地区办学。另一项计划则通过向家长分发教育券,使贫民窟的失学儿童能够进入PEF认可的机构学习。一些学校的招生名额被全部买断。这些学校不能收费,且必须接受教学管理和教师培训。

Although the funding per pupil is less than half of what is spent by state schools, results are at least as good, says Aneela Salman, PEF’s managing director. “The private sector can be much more flexible about who it hires, and can set up schools quickly in rented buildings and hire teachers from the local community.”

据PEF总经理Aneela Salman说,尽管这些学校在每位学生身上花费的资金不足公立学校的一半,结果却并不比公立学校差。“私人领域的雇用更具弹性,可以租用校舍快速组建学校,还可从当地居民中招募教师。”

Crucially, the province is also improving oversight and working out how to inform parents about standards. It has dispatched 1,000 inspectors armed with tablet computers to conduct basic checks on whether schools are operating and staff and children are turning up. They have begun quizzing teachers, using questions from the exams they are meant to be teaching their pupils to pass. The early results, says one official grimly, are “not good”.

殊为关键的是,旁遮普省还在改善监管,并想方设法告知家长学业水平。全省派出了1000名配备平板电脑的检查员,针对学校是否正常运行、员工与学生是否在校的问题进行基本的检查。他们使用本应由教师教授并用于测试学生的考试题目,开始对教师进行测试。一位官员阴沉地表示,早期结果“并不乐观”。

In a joint study by the World Bank, Harvard University and Punjab’s government, parents in some villages were given report cards showing the test scores of their children and the average for schools nearby, both public and private. A year later participating villages had more children in school and their test scores in maths, English and Urdu were higher than in comparable villages where the cards were not distributed. The scheme was very cheap, and the improvement in results larger than that from some much pricier interventions, such as paying parents to send their children to school.

在由世界银行、哈佛大学和旁遮普省政府联合开展的一项研究中,学生的成绩报告被分发到一些村庄的家长手中,与之一同下发的还有附近各公私立学校的平均成绩。一年后,与没有分发成绩报告的可比村庄相比,受调查村庄的入学率得到了提高,当地学生的数学、英语和乌尔都语成绩也都更高。这些举措花费很少,但相比其他昂贵的干预措施,比如付钱要求家长送子女入学,其结果却更优。

PEF now educates 2m of Punjab’s 25m children, a share likely to grow by another million by 2018. Meanwhile the number of state schools has fallen by around 2,000 as some have been merged and others closed.

在旁遮普省2500万名儿童中,已有200万人通过PEF获得了教育,到2018年,这个人数很可能再增加100万。与此同时,公立学校的数量已减少了约2000家,一些被合并,还有些已经关门。

Such a wholesale shift to private-sector provision would create a storm of protest in Britain, whose Department for International Development is backing Punjab’s reforms. But there are few signs of anxiety in a country where many parents aspire to send their children to a private school and the country’s recent Nobel laureate, the education activist Malala Yousafzai, is the daughter of a private-school owner.

尽管英国国际发展部是旁遮普改革的幕后推手,但如此大规模地转向私人部门如果发生于英国,结果只会是一场抗议浪潮。然而在巴基斯坦,焦虑情绪则几乎看不到,因为该国的许多父母正在为将子女送入私立学校积极努力。这个国家最近的诺贝尔奖得主,教育活动家马拉拉·优素福扎伊本人,就是一名私立学校老板之女。

Schooling on tick

贷款办学

NGOs and education activists often oppose the spread of private schools, sometimes because they fear the poorest will be left behind, but often because of ideology. In October Kishore Singh, the UN special rapporteur on the right to education, told the UN General Assembly that for-profit education “should not be allowed in order to safeguard the noble cause of education”. Others, seemingly more reasonably, demand greater oversight of the sector: in a resolution on July 1st the UN Human Rights Council urged countries to regulate and monitor private schools.

NGO和教育活动家群体往往反对私立学校扩张,部分出于对底层人群无法获得入学机会的担心,更多则是观念差异。十月,联合国受教育权特别调查员Kishore Singh向联合国大会报告称,盈利性教育“应被禁止,否则将无法保卫崇高的教育事业。”另外一些貌似更为合理的意见,则提出对这一部门开展更严厉的监管:在7月1日的一份决议中,联合国人权理事会要求各国监管私立学校。

But where governments are hostile to private schools, regulation is often a pretext to harass them. And many of the criteria commonly used, such as the quality of facilities, or teachers’ qualifications and pay, have been shown by research in several countries to have no bearing on a school’s effectiveness. In recent years many poor countries staffed state schools with unqualified teachers on temporary contracts, paying them much less than permanent staff. In India, Kenya, Pakistan and Mali their pupils learn at least as much as those taught by permanent teachers.

然而,如果一地政府对私立学校持否定态度,此时的监管就成为了骚扰的借口。数国开展的研究显示,许多常用的评价标准,诸如设施质量、教师资格和收入,与教学成果之间无甚关联。近年来,许多贫困国家为填补公立学校的人员短缺,与资历不足者签订临时合同,以远低于编内员工的薪水雇用了一批教师。在印度、肯尼亚、巴基斯坦和马里,相比编内教师,由临时教师教授的学生并未产生知识短缺的问题。

Many small private schools do not try to get on any official register, knowing that they have no chance of succeeding, not least because of widespread corruption. A federal law from 2009 means that all private schools in India must be registered. This means satisfying onerous conditions, to which states have added their own.

许多小型私立学校已知没有可能得到官方注册,干脆放弃尝试,这其中,腐败是一个很重要的原因。印度2009年颁布的一项联邦法律规定,所有私立学校都必须注册。这意味着各式各样的苛刻条件,以及各邦独特的额外规定。

They must have access to playgrounds (immediately barring almost all those in urban slums), and qualified teachers who are paid salaries that match government-run schools. The state of Uttar Pradesh limits tuition-fee increases to 10% every three years. The main effect of this blizzard of bureaucracy has been to provide corrupt officials with a new excuse to seek bribes.

注册条件之一是有能力提供操场(几乎所有城市贫民区的学校都被立即排除),另一条则要求已获资格认证、薪酬达到公立学校水平的教员。北方邦规定三年内学费增长不得超过10%。这场官僚风暴的主要成就,是为腐败官员提供了索贿的新途径。

The need to fly under the radar means that schools lack access to credit and cannot grow or reap economies of scale. One small study in rural India found that a quarter of private schools visited by researchers had closed down when they returned a year later. Some will have been sound businesses brought down by cash-flow problems, as parents with precarious, low-paid jobs struggled to pay the fees. Others will have been run by people with an enthusiasm for education, but no business acumen.

被迫在监管刀口下求存,使得学校无从取得贷款,无力发展,更难以实现规模经济。一项针对印度乡村的小型研究显示,受调查的私立学校中有四分之一在一年后关门。一些本应健康发展的学校因现金流问题而倒闭,其资金来源是无稳定工作、收入颇低的学生家长。另一些学校的经营者空有投身教育的热情,却无商业头脑。

Another study in Punjab shows how much the lack of credit hamstrings private schools. All those in some randomly selected villages were given a $500 grant and asked to submit proposals for using the money to improve, just as a bank might demand a business plan in return for a small loan. Audits a year later found that the grants had been entirely spent on school improvements and test scores had risen more than in a control group of villages.

开展于旁遮普省的另一项研究则显示了,贷款短缺如何妨碍私立学校的发展。随机选择一些村庄,向其中所有私立学校给予500美元的赞助,然后如同银行提供小额贷款时索要商业计划书一样,要求其提供这笔钱的用途。一年后,审计发现赞助金完全被用于改善学校条件,考试成绩也与作为对照组的另一村庄相比有更大进步。

A promising development is the spread of low-cost for-profit school chains in big cities in Africa and south Asia. Some started by catering to better-off families and are now moving into the mass market. Their founders have more in common with the highly educated young enthusiasts who start charter schools in America than the owners of the single institutions that dominate the sector, says Julia Moffett of the Future of Learning Fund, which backs education entrepreneurs in Africa.

在非洲和南亚,一些大城市出现了廉价的盈利性连锁学校,这让人看到了未来的希望。其中一些学校一开始以富裕家庭为受众,现在也已进入大众市场。“学习的未来”基金会的Julia Moffett说,与在该领域内占主导地位的独体机构的拥有者相比,这些学校的创办者更像在美国创办特许学校的年轻人,他们受过高等教育,对教育事业充满热忱。“学习的未来”基金会旨在向非洲的教育企业家提供援助。

Bridge International Academies, which runs around 400 primary schools in Kenya and Uganda, and plans to open more in Nigeria and India, is the biggest, with backers including Facebook’s chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, and Bill Gates. Omega Schools has 38 institutions in Ghana. (Pearson, which owns 50% of The Economist, has stakes in both Bridge and Omega.) Low-cost chains with a dozen schools or fewer have recently been established in India, Nigeria, the Philippines and South Africa.

桥国际连锁学院在肯尼亚和乌干达经营有约400家小学,正打算进军尼日利亚和印度。这是诸多廉价连锁学校中规模最大的一家,其支持者包括Facebook首席执行官马克·扎克伯格以及比尔·盖茨。Omega Schools在加纳拥有38家机构。(拥有《经济学人》50%股份的Pearson集团,在上述两家企业都有股份。)近来,一些连锁数量在10个左右甚至更少的廉价连锁学校,已经在印度、尼日利亚、菲律宾和南非出现。

Bridge’s cost-cutting strategies include using standardised buildings made of unfinished wooden beams, corrugated steel and iron mesh, and scripted lessons that teachers recite from hand-held computers linked to a central system. That saves on teacher training and monitoring.

在桥国际学院,校舍以半成品木梁、波纹钢和铁网为建筑材料,依照标准统一建造;教师使用手持电脑连通中央系统,下载预定的课程内容背诵备用。这些举措不仅缩减了开支,还省去了对教师的培训和监管。

An independent evaluation is under way to find out whether such robo-teaching is better than the alternative—too often ill-educated teachers struggling through material they do not understand themselves. The potential of technology to transform education is unlikely to be realised in state institutions, where teachers and unions resist anything that might increase oversight or reduce the need for staff.

学业不精的老师为了备课费尽心思,这种情况常有;与其如此,是否照本宣科的教学方式更为优越?为了解答这一问题,一项独立研究正在进行当中。在公立学校,任何加强监管或减少人员需求的举措,都会遭到教师和工会的抵制,因此技术改变教育的潜能难以在公立学校发挥。

Another trend, says Prachi Srivastava of the University of Ottawa, is the emergence of providers of auxiliary services for private schools, including curriculum development, science kits and school-management training. Credit facilities are also cropping up. The Indian School Finance Company, funded by Grey Ghost Ventures, an Atlanta-based impact investor, has expanded to six Indian states since it started in 2009.

渥太华大学的Prachi Srivastava说,面向私立学校提供辅助服务的行业正在兴起,服务内容包括课程安排、教学用具以及学校管理方面的训练。信贷服务也在悄然出现。创立于2009年的印度学校金融公司,由总部位于亚特兰大的影响力投资商Grey Ghost Ventures投资,现已扩展至印度六个邦。

The IDP Rising Schools Programme, a small-loans programme in Ghana, also offers its clients teacher training. Private schooling may turn out to be good business for these firms and their investors—and, if governments allow it to flourish, for pupils, too.

出现于加纳的一项小额借贷项目,IDP Rising Schools Programme,同时也向其客户提供教师培训服务。对于企业和投资者来说,私立学校这一行可能前途光明;如果各国政府允许其充分发展,学生群体也将从中受惠。

翻译:sheperdmt([email protected]),易海([email protected])

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

编辑:辉格@whigzhou