Divided by DNA:

The uneasy relationship between archaeology and ancient genomics

DNA 分歧:考古学与古基因组学之间的不稳定关系

Two fields in the midst of a technological revolution are struggling to reconcile their views of the past. Ancient genomes are revolutionizing the study of human prehistory but sometimes straining the relationships between archaeologists and geneticists.

在技术变革中,两个研究领域正在努力调和他们对历史的看法。古基因组正在彻底改变人类史前史的研究,但有时会使考古学家和遗传学家之间的关系变得紧张。

Thirty kilometres north of Stonehenge, through the rolling countryside of southwestEngland, stands a less-famous window into Neolithic Britain. Established around 3600 BC by early farming communities, the West Kennet long barrow is an earthen mound with five chambers, adorned with giant stone slabs. At first, it served as a tomb for some three dozen men, women and children. But people continued to visit for more than 1,000 years, filling the chambers with relics such as pottery and beads that have been interpreted as tributes to ancestors or gods.

穿过英格兰西南部绵延的乡村,一座矗立于巨石阵以北30公里处的遗址让人一窥新石器时代的英国。West Kennet长冢(long barrow)【译注:新石器时代早期常见于西欧的标志类建筑,一般由泥土和石头构成,用作坟墓】由远古的农业社区于公元前3600年左右建成,它包含一个土墩和五个室,以巨大的石板装饰。起初,长冢是30多个男人,女人和孩子的坟墓。但在随后的1000多年时间里,不断地有人访问长冢,在五个室内放满了陶器和珠子等文物,这些文物被认为是对祖先或神灵的敬献。

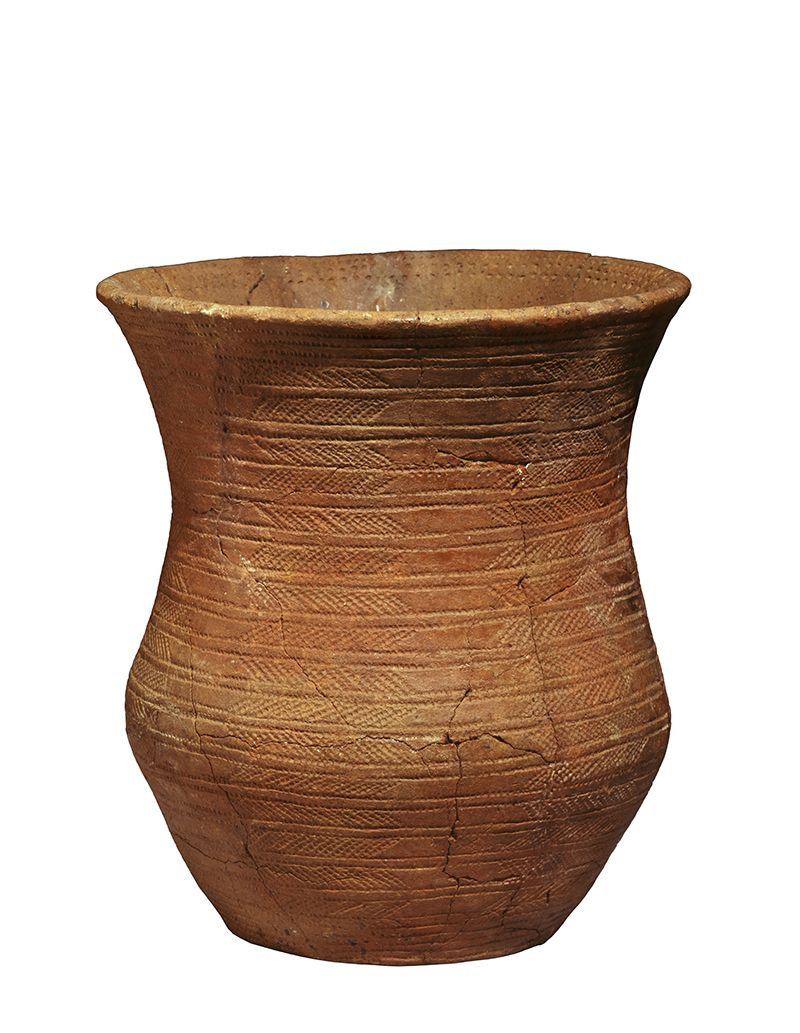

The artefacts offer a view of those visitors and their relationship with the wider world. Changes in pottery styles there sometimes echoed distant trends in continental Europe, such as the appearance of bell-shaped beakers — a connection that signals the arrival of new ideas and people in Britain. But many archaeologists think these material shifts meshed into a generally stable culture that continued to follow its traditions for centuries.

这些文物为研究长冢的古代访客,以及他们与外部更广阔世界之间的联系提供了一个切入点。英格兰长冢中陶器风格的变化,有时会与遥远欧洲大陆上的陶器风格趋势相呼应:例如钟形杯的诞生,标志着有新的人群和新的观念来到不列颠。但许多考古学家认为,这些器物的改变与一种大致稳定的文化相吻合,这一文化在数世纪中一直遵循其传统。

“The ways in which people are doing things are the same. They’re just using different material culture — different pots,” says Neil Carlin atUniversity College Dublin, who studies Ireland and Britain’s transition from the Neolithic into the Copper and Bronze Ages.

“人们做事的方式是一样的。他们只是使用不同的器物文化,不同的陶罐”,柏林大学的Neil Carlin说。他研究爱尔兰和不列颠从新石器时代到黄铜和青铜时代的变迁。

But last year, reports started circulating that seemed to challenge this picture of stability. A study analysing genome-wide data from 170 ancient Europeans, including 100 associated with Bell Beaker-style artefacts, suggested that the people who had built the barrow and buried their dead there had all but vanished by 2000 BC. The genetic ancestry of Neolithic Britons, according to the study, was almost entirely displaced. Yet somehow the new arrivals carried on with many of the Britons’ traditions. “That didn’t fit for me,” says Carlin,who has been struggling to reconcile his research with the DNA findings.

但去年,一些研究报道开始流传,似乎挑战了这种文化稳定的图景。一项研究分析了来自170名古代欧洲人的全基因组数据,其中有100名古代欧洲人与West Kennet长冢中的钟杯(Bell Beaker)文化【译注:又音译为比克文化,指兴于新石器时代晚期,终于青铜时代早期,分布于中欧和西欧的一种古代文化,以使用钟形陶杯为特点。】文物有关。这一研究表明,建造长冢并埋葬死者的人在公元前2000年就几乎消失殆尽了。根据该研究,新石器时代不列颠住民的遗传学祖先已几乎完全被取代。然而不知何故,后来的人继承了许多不列颠原住民的传统。“这和我的研究结果不一致”,Carlin说,他一直在努力调和他的研究与DNA研究的发现。

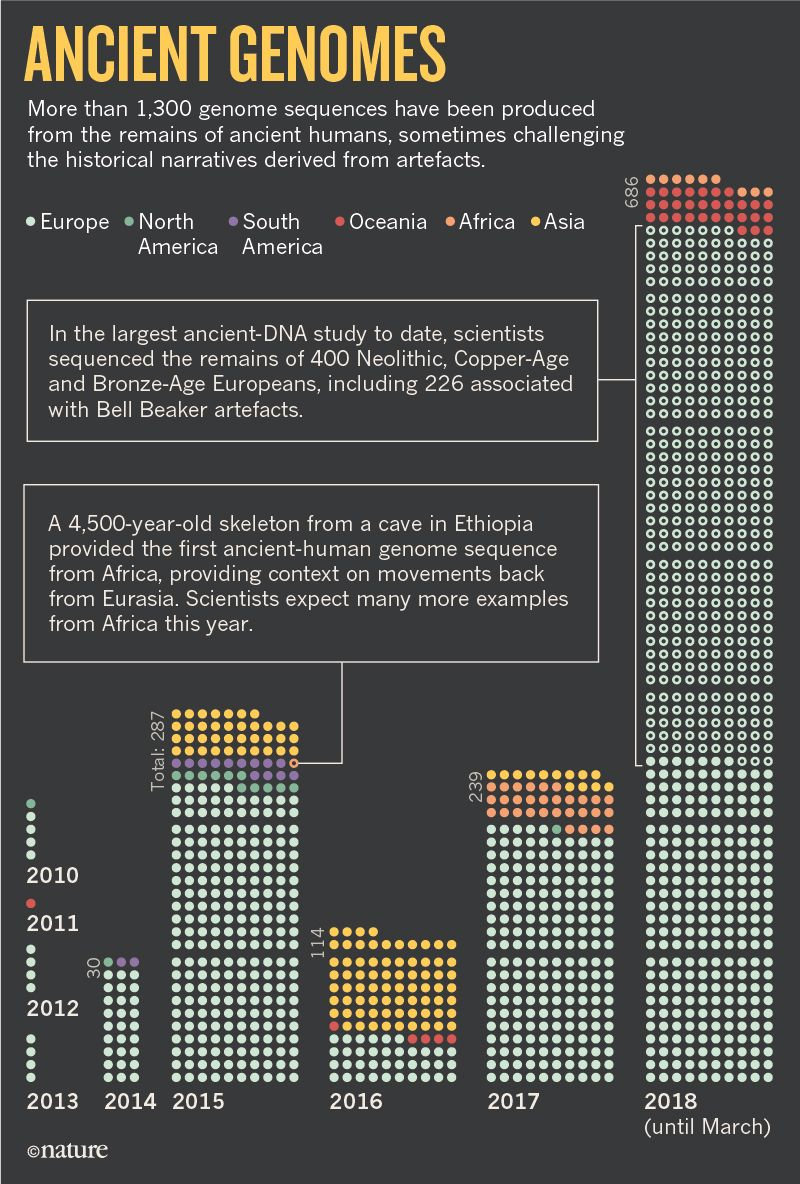

The Bell Beaker ‘bombshell’ study appeared in Nature in February and included 230 more samples, to make it the largest ancient-genome study on record. But it is just the latest example of the disruptive influence that genetics has had on the study of the human past. Since 2010, when the first ancient-human genome was fully sequenced, researchers have amassed data on more than 1,300 individuals (see ‘Ancient genomes’ graphic), and used them to chart the emergence of agriculture, the spread of languages and the disappearance of pottery styles — topics that archaeologists have laboured over for decades.

关于钟杯文化的重磅研究刊登在二月份的Nature杂志上。这项研究包括了230多个样本,使其成为有记录以来规模最大的古基因组研究。但它只是遗传学技术的引入对古人类研究造成颠覆性影响的一个最新例证而已。自2010年第一个古人类基因组完全测序以来,研究人员已经收集了超过1300个人的基因组数据(参见“古基因组图”),并用它们来描绘农业的出现,语言的传播以及陶器的风格的消逝,这些都是考古学家几十年来一直大力研究的课题。

Some archaeologists are ecstatic over the possibilities offered by the new technology. Ancient-DNA work has breathed new life and excitement into their work, and they are beginning once-inconceivable investigations, such as sequencing the genome of every individual from a single graveyard. But others are cautious.

一些考古学家对新技术提供的可能性感到欣喜若狂。古代DNA的研究成果让他们的研究焕发了新生,为他们带来了新的兴趣。这些考古学家开始了曾经无法想象的调查:例如对一个墓地内每个人的基因组进行测序。但其他人则持谨慎态度。

“Half the archaeologists think ancient DNA can solve everything. The other half think ancient DNA is the devil’s work,” quips Philipp Stockhammer, a researcher at Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, Germany, who works closely with geneticists and molecular biologists at an institute in Germany that was set up a few years ago to build bridges between the disciplines. The technology is no silver bullet, he says, but archaeologists ignore it at their peril.

“一半的考古学家认为古代DNA可以解决所有问题。另一半人认为古代DNA是魔鬼之作”,德国慕尼黑路德维希·马克西米利安大学的研究人员Philipp Stockhammer如是说。他一研究所内的德国遗传学家和分子生物学家密切合作,这一几年前成立的研究所致力于建立学科之间的桥梁。他说,这项技术并不是灵丹妙药,可一些考古学家却遗憾地忽视了它的存在。

Some archaeologists, however, worry that the molecular approach has robbed the field of nuance. They are concerned by sweeping DNA studies that they say make unwarranted, and even dangerous, assumptions about links between biology and culture. “They give the impression that they’ve sorted it out,” says MarcVander Linden, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, UK. “That’s a little bit irritating.”

然而,考古学家们担心分子研究方法已经对这一细节中见真章的学科造成了破坏。他们担心全面推行的DNA研究会对生物学和文化之间的联系做出毫无根据,甚至是危险的假设。英国剑桥大学的考古学家Marc VanderLinden说:“那些研究人员给人的印象是,他们已经把这个领域的问题全都梳理清楚了。这有点令人不快。”

This isn’t the first time archaeologists have had to contend with transformative technology. “The study of prehistory today is in crisis,” wrote Cambridge archaeologist Colin Renfrew in his 1973 book Before Civilization, describing the impact of radiocarbon dating. Before the technique was developed by chemists and physicists in the 1940s and 50s, prehistorians determined the age of sites using ‘relative chronologies’, in some cases relying on ancient Egyptian calendars and false assumptions about the spread of ideas from the Near East. “Much of prehistory, as written in the existing textbooks is inadequate: some of it, quite simply wrong,” Renfrew surmised.

这已经不是考古学家们第一次不得不面对变革性技术了。剑桥考古学家Colin Renfrew在其1973年出版的《文明之前》(Before Civilization)一书中这样描述碳定年法【译注:利用放射性碳14元素进行年代测定。】对考古学的影响:“目前,史前史研究正处于危机之中。”在1940和1950年代化学家和物理学家研发出该技术之前,史前史研究人员一般使用相对年表法(relative chronologies)【译注:通过研究未知遗址与已知年代文物的关系,确定遗址年代的方法。】确定遗址的年代,而这在一些情况下依赖于古埃及的历法,还有关于近东思想传播过程的错误假设。“现有教科书中所写的大部分史前史都是不充分的,其中一些完全错误”,Renfrew推测。

It wasn’t an easy changeover — early carbon-dating efforts were off by hundreds of years or more — but the technique eventually allowed archaeologists to stop spending most of their time worrying about the age of bones and artefacts and focus instead on what the remains meant, argues Kristian Kristiansen, who studies the Bronze Age at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. “Suddenly there was a lot of free intellectual time to start thinking about prehistoric societies and how they are organized.” Ancient DNA now offers the same opportunity, says Kristiansen, who has become one of his field’s biggest cheerleaders for the technology.

在瑞典哥德堡大学研究青铜时代的Kristian Kristiansen认为,这样的转变不是一帆风顺的,因为早期的碳14年代测定法有上百年甚至更长时间的误差,但这项技术最终还是让考古学家不必再花费大部分时间来担心骨骼和人工制品的年代,而是将注意力集中在遗迹的意义上。“突然就有了很多自由的研究时间,可以用于研究史前社会以及它们是如何组织起来的。”现在,古代DNA提供了同样的机会,Kristiansen说,他已是自己研究领域中古代DNA技术最大的拥护者之一。

古代基因组

古代基因组

Genetics and archaeology have been uneasy bedfellows for more than 30 years — the first ancient-human DNA paper, in 1985, reported sequences from an Egyptian mummy(now thought to be contamination). But improvements in sequencing technology in the mid-to-late 2000s set the fields on a collision course.

30多年来,遗传学和考古学一直是不稳定的伙伴。早在1985年,第一本古人类DNA论文就报道了埃及木乃伊的序列(现在这一序列被认为遭到了污染)。但在20世纪中后期,测序技术的改进使这两个领域陷入了冲突。

In 2010, scientists led by Eske Willerslev at the Natural History Museum ofDenmark used DNA from a lock of hair from a 4,000-year-old native Greenlander to generate the first complete sequence of an ancient-human genome. Seeing the future of the field before his eyes, Kristiansen asked Willerslev to team up on a prestigious European Research Council grant that would allow them to examine human mobility as the late Neolithic gave way to the Bronze Age, some 4,000–5,000 years ago.

2010年,丹麦自然历史博物馆科学家Eske Willerslev带领的研究团队利用来自4000年前原始格陵兰人一缕头发中的DNA来生成古人类基因组的第一个完整序列。Kristiansen看到了这个领域的未来,他请求与Willerslev联合,从欧盟研究理事会那里申请一项著名的基金,来研究新石器时代晚期至青铜时代早期,大约4000—5000年前人类的流动和迁移。

Association problems

合作的麻烦

Migration has been a major source of tension for archaeologists. They have debated at length whether human movements are responsible for cultural changes in the archaeological record, such as the Bell Beaker phenomenon, or whether it is simply the ideas that are moving through cultural exchanges. Populations identified by the artefacts they associated with came to be seen as a remnant of the science’s colonial past, and one that imposed artificial categories. “Pots are pots, not people,” goes a common refrain.

人类的迁移一直是考古学家紧张的主要来源。他们详细讨论了考古记录中的文化变迁是就像钟杯现象【译注:又译为贝尔陶器现象,指前文所述的外来移民在人口结构上大规模取代当地原住民,而在文化上保留了当地特色的现象】那样,由人类迁移直接导致,还是这样的变迁只是文化观点的交流所致。通过一些相关人工制品就定义一个人类种群,这已被视为是过去科学殖民观念【译注:未经仔细考虑,就将科学中的方法和“先进的”观点直接应用于其他学科】的残留,而且这种做法还扩大了分类中的人为因素。“陶器只是陶器,而不是人”,这是老生常谈了。

钟杯陶器

钟杯陶器

BellBeaker pots signal a period of unprecedented cultural intermingling for earlyEuropeans. [Figure 2 description]

钟杯陶器标志着早期欧洲人前所未有的文化融合时期

Most archaeologists have since cast aside the view that prehistory was like a game of Risk, in which homogenous cultural groups conquer their way across a map of the world. Instead, researchers tend to focus on understanding a small number of ancient sites and the lives of the people who lived there. “Archaeology had moved away from these grand narratives,” says Tom Booth, a bioarchaeologist at the Natural History Museum in London, who is part of a team using ancient DNAto trace the arrival of farming in Britain. “A lot of people thought you needed to understand change regionally to understand people’s lives.”

大多数考古学家从此抛弃了史前史就像是一场“战国风云”【译注:一款即时战略桌游】的观点,在这种观念中,同质的文化群体会在整个世界范围内扩张他们的地盘。相反,研究人员倾向于集中精力了解少数古代遗址和遗址中居民的生活。伦敦自然历史博物馆的生物考古学家Tom Booth说:“考古学已经摆脱了这些宏大的叙事,大家都认为你必须了解人们所在局部地区的变化,才能去理解当时人们的生活。”他所在的团队利用古代DNA追踪农业在不列颠的出现过程。

Ancient-DNA work — which has repeatedly shown that a region’s modern inhabitants are often distinct from populations that lived there in the past — promised, for better or worse, to bring back some of the broad focus on migration to human prehistory. “What genetics is particularly good at is detecting change in populations,” says David Reich, a population geneticist at Harvard MedicalSchool in Boston, Massachusetts. Archaeologists, Kristiansen says, “were prepared to accept that individuals had travelled”. But for the Bronze Age period that he studies, “they were not prepared for major migrations. That was a new thing.”

古代DNA相关的研究工作曾多次表明,一个地区的现代居民往往与过去居住的种群不一致。无论好坏,古代DNA相关的研究工作都会把一些广泛的研究重点拉回到史前人类的迁移上。“遗传学特别擅长检测种群的变化”,马萨诸塞州波士顿哈佛医学院的群体遗传学家DavidReich说。Kristiansen说,考古学家们“已经准备好接受少部分人群曾经长距离迁移这件事”,但在他所研究的青铜时代领域中,“考古学家们还没有准备好接受大规模的人口迁移,这种观点太新颖了”。

Studies of strontium isotopes in teeth, which vary with local geochemistry, had hinted that some Bronze Age individuals had moved hundreds of kilometres over their lifetimes, Kristiansen says. He and Willerslev wondered whether DNA analysis might detect movements of whole populations during this period.

Kristiansen说,一项关于古人类牙齿中锶同位素-它会随着地区地质化学的变化而变化-的研究暗示了一些青铜时代的古人类人在其一生中已经迁移了数百公里。他和Willerslev想知道DNA分析是否可以检测到这一时期整个人类种群的流动。

They would have competition. In 2012, David Anthony, an archaeologist at HartwickCollege in Oneonta, New York, loaded his car with boxes of human remains that he and his colleagues had excavated from the steppes near the Russian city ofSamara, including bones associated with a Bronze Age pastoralist culture called the Yamnaya. He was bringing them to the ancient-DNA lab just established byReich in Boston. Like Kristiansen, Anthony was comfortable theorizing about the past on a grand scale. His 2007 book The Horse, the Wheel and Language proposed that the Eurasian steppe had been a melting pot for the modern developments of horse domestication and wheeled transport, which propelled the spread of a family of languages calledIndo-European across Europe and parts of Asia.

他们会面临竞争。2012年,来自纽约州Oneonta市Hartwick学院的考古学家David Anthony将他和他的同事们从俄罗斯萨马拉市附近草原上发掘出的人类遗物装上汽车,这些遗物中包括一些人类遗骨,属于青铜时代的Yamnaya游牧文化。Anthony将这些遗骨带到了Reich在波士顿建立的古DNA实验室。和Kristiansen一样,在全球的大尺度上提出一个人类史前史的理论对Anthony而言并不困难。他在2007年出版的《马,轮子和语言》(The Horse, the Wheel and Language)一书中提出,欧亚草原是马匹驯化和轮式运输工具发展的熔炉,这推动了欧洲和亚洲部分地区印欧语系各语言的传播。

In duelling 2015 Nature papers, the teams arrived at broadly similar conclusions: an influx of herders from the grassland steppes of present-day Russia and Ukraine — linked to Yamnaya cultural artefacts and practices such as pit burial mounds — had replaced much of the gene pool of central and Western Europe around 4,500–5,000 years ago. This was coincident with the disappearance of Neolithic pottery, burial styles and other cultural expressions and the emergence of Corded Ware cultural artefacts, which are distributed throughout northern and central Europe. “These results were a shock to the archaeological community,” Kristiansen says.

2015年,两个团队各自在《自然》杂志中发表了他们的研究论文。他们得出了大体相似的结论:一批古代牧民涌入了今属俄罗斯和乌克兰草原,他们大约在4500—5000年前就已经取代了大部分中欧和西欧的基因库,而这些牧民正好与Yamnaya文化中的手工制品和坑葬墓等生活习俗有关。这一事件与欧洲新石器时代陶器、墓葬风格和其他文化表现的消失,以及普遍分布于中欧和北欧的绳纹器文化(Corded Ware cultural)【译注:又称战斧文化,指兴于新石器时代晚期,盛于黄铜时代,终于青铜时代早期,广泛分布于莱茵河以西至伏尔加河以东的中欧、北欧地区的古代文化。】艺术品的诞生恰巧同时发生。“这些结果令考古学界感到震惊”,Kristiansen说。

Cord cutters

诘难者

The conclusions immediately met with push-back. Some of it began even before the papers were published, says Reich. When he circulated a draft among his dozens of collaborators, several archaeologists quit the project. To many, the idea that people linked to Corded Ware had replaced Neolithic groups in WesternEurope was eerily reminiscent of the ideas of Gustaf Kossinna, the early-twentieth-century German archaeologist who had connected Corded Ware culture to the people of modern Germany and promoted a ‘Risk board’ view of prehistory known as settlement archaeology. The idea later fed into Nazi ideology.

这一结论立刻受到了回击。Reich说,有些回击甚至在论文发表前就开始了。在他给数十位合作者中传阅论文草稿时,就有几位考古学家退出了这个项目。对许多人而言,绳纹器文化相关的人类群体取代了西欧原本的新石器时代人类群体,这一想法会令人想起Gustaf Kossinna的观点。Kossinna是二十世纪早期的德国考古学家,他将绳纹器文化与现代德国人民联系起来,并将此升华为一种对史前史的“战国风云”式的视角,后来被称作“定居点考古学”【译注:Kossinna认为,明确界定的考古文化区域必然与某个人群或部落的活动区域相对应】。这个观点后来被纳入纳粹的意识形态。

Reich won his co-authors back by explicitly rejecting Kossinna’s ideas in an essay included in the paper’s 141-page supplementary material. He says the episode was eye-opening in showing how a wider audience would perceive genetic studies claiming large-scale ancient migrations.

在论文141页补充材料里的一篇文章中,Reich明确拒绝了Kossinna的观点,这让他赢得了论文共同作者的支持。Reich说,这个插曲展示了更多的受众会如何看待那些声称古代存在大规模人口迁移的基因研究,让他大开眼界。

Still, not everyone was satisfied. In an essay titled ‘Kossinna’s Smile’,archaeologist Volker Heyd at the University of Bristol, UK, disagreed, not with the conclusion that people moved west from the steppe, but with how their genetic signatures were conflated with complex cultural expressions. CordedWare and Yamnaya burials are more different than they are similar, and there is evidence of cultural exchange, at least, between the Russian steppe and regions west that predate Yamnaya culture, he says. None of these facts negates the conclusions of the genetics papers, but they underscore the insufficiency of the articles in addressing the questions that archaeologists are interested in,he argued. “While I have no doubt they are basically right, it is the complexity of the past that is not reflected,” Heyd wrote, before issuing a call to arms. “Instead of letting geneticists determine the agenda and set the message, we should teach them about complexity in past human actions.”

不过,并非所有人都对此满意。在一篇题为《Kossinna的微笑》(Kossinna’s Smile)的文章中,英国布里斯托尔大学的考古学家Volker Heyd并不反对人群从草原向西迁移的结论,但对人群的基因特征如何与复杂的文化表现形式结合在一起持有异议。他说,绳纹器文化和Yamnaya文化墓葬之间的不同点要多于他们的相同点。因为在Yamnaya文化出现前就有证据表明,至少俄罗斯草原及其西部地区之间存在文化交流。他认为,这些事实并不会否定那篇遗传学论文的结论,但会导致文章在解决考古学家感兴趣的问题方面得分不足。“虽然我确信他们基本上是正确的,但远古历史的复杂性在文中并没有得到反映。我们不应该让遗传学家决定研究日程和具体的研究内容,而应该告诉他们古代人类行为的复杂性。” Heyd在发出呼吁之前写道。

Ann Horsburgh, a molecular anthropologist and prehistorian at Southern MethodistUniversity in Dallas, Texas, attributes such tensions to communication problems. Archaeology and genetics say distinct things about the past, butoften use similar terms, such as the name of a material culture. “It’s C. P. Snow all over again,” she says, referring to the influential ‘Two Cultures’ lectures by the British scientist lamenting the deep intellectual divide between the sciences and the humanities. Horsburgh complains that genetic results are too often given precedence over inferences about the past from archaeology and anthropology, and that such “molecular chauvinism” prevents meaningful engagement. “It’s as though genetic data, because they’re generated by people in lab coats, have some sort of unalloyed truth about the Universe.”

Ann Horsburgh是德克萨斯州达拉斯南方卫理公会大学的分子人类学家和史前史学家,她将这种考古学与遗传学之间的紧张关系归因于沟通问题。考古学和遗传学经常使用相同的术语来讨论实际相去甚远的东西,例如某个器物文化的名称。“查尔斯·P·斯诺所说的事又一次出现了”,她指的是那位英国科学家影响深远的“两种文化”演讲,陈述了科学与人文之间所存在深刻的知识鸿沟【译注: C. P. Snow,20世纪英国科学家、作家,他于1959年在剑桥大学发表主题为“两种文化与科学变革”的演讲,认为知识体系被人为划分成“人文”和“科学”两个领域,两者之间存在鸿沟,难以相互理解,这一点需要改变】。Horsburgh抱怨相对考古学和人类学对过去的推测,遗传学的研究成果往往被置于优先的地位,而这种“分子沙文主义”阻碍了其他研究者们发表有意义的讨论。“像基因数据一样,它们出自那些实验室里穿白大褂的专家,因而多少被视作纯粹的真理。”

Horsburgh,who is seeing her own field of African prehistory start to feel the tremors of ancient genomics, says that archaeologists frustrated at having their work misinterpreted should wield their power over archaeological remains to demand more equitable partnerships with geneticists. “Collaboration doesn’t mean I send you an e-mail saying ‘hey, you’ve got some really cool bones. I’ll get you a Nature paper.’ That’s not a collaboration,” she says.

Horsburgh所研究的非洲史前史领域已经开始受到古基因组技术的冲击。她说,考古学家对于他们的工作被误解而感到沮丧,他们应该强化自己在遗址考古方面的力量,从而要求与遗传学家们建立更平等的合作关系。“合作并不是我给你发一封电子邮件,说‘嘿,你有一些非常酷的遗骨。我们可以合作可以在自然杂志上发表一篇论文’,那并不是合作。”她说。

Many archaeologists are also trying to understand and engage with the inconvenient findings from genetics. Carlin, for instance, says that the Bell Beaker genome study sent him on “a journey of reflection” in which he questioned his own views about the past. He has pored over the selection of DNA samples included in the study as well as the basis for its conclusion that the appearance ofBell Beaker artefacts coincided with a greater than 90% replacement inBritain’s gene pool. “I didn’t want to be questioning it from a position of ignorance,” Carlin says.

许多考古学家也试图去理解并研究这些让他们不舒服的遗传学发现。例如Carlin就说道,钟杯现象相关的遗传学研究结果让他来了一次“学术反思之旅”,质疑了自己对史前史的看法。他仔细梳理了这项研究中所涉及的DNA样本的筛选过程,这也是整个研究结论的基础,即钟杯现象的出现与古代不列颠基因库中超过90%被替代恰巧在同时发生。“我不想无知地质疑结果”,Carlin说。

LikeHeyd, he accepts that a shift in ancestry occurred (although he has questions about its timing and scale). Those results, in fact, now have him wondering about how cultural practices such as leaving pottery and other tributes at theWest Kennet long barrow persisted in the face of such upheavals. “I would characterize a lot of these papers as ‘map and describe’. They’re looking at the movement of genetic signatures, but in terms of how or why that’s happening, those things aren’t being explored,” says Carlin, who is no longer disturbed by the disconnect. “I am increasingly reconciling myself to the view that archaeology and ancient DNA are telling different stories.” The changes in cultural and social practices that he studies might coincide with the population shifts that Reich and his team are uncovering, but they don’t necessarily have to. And such biological insights will never fully explain the human experiences captured in the archaeological record.

像Heyd一样,Carlin接受了古代欧洲原住民曾被取代这一事实(虽然他对取代发生的时间和规模仍抱有疑问)。实际上,这一结果反而让他去思考,为何在面临如此的动荡之时,原住民在West Kennet长冢里敬献陶器和其他贡品的文化习俗仍然能保留下来。“我会把很多关于这方面的论文划归为‘路线描绘和说明’。这些论文讨论了基因特征的迁移路线,但对迁移这一事件为何发生又如何发生,它们并没有进行探索,”Carlin说。现在,他已不再受这种脱节的干扰:“我越来越强烈地认同这一观点,即考古学研究和古基因组学研究讲述的是不同的故事。” Carlin所研究的文化和社会行为的变化,可能与Reich及其团队揭示的种群变化恰巧同时发生,但也并不是一定同时发生。这样的生物学视角一直注定不能完全解释考古记录中发现的人类活动。

Reich agrees that his field is in a “map-making phase”, and that genetics is only sketching out the rough contours of the past. Sweeping conclusions, such as those put forth in the 2015 steppe migration papers, will give way to regionally focused studies with more subtlety.

Reich同意他的研究领域尚属于Carlin所说的“描绘路线阶段”,遗传学只是勾勒出史前史的粗略轮廓。那些全面而概述的观点,例如2015年关于草原移民的论文结论,将会让位于更细致更具体的特定区域研究。

This is already starting to happen. Although the Bell Beaker study found a profound shift in the genetic make-up of Britain, it rejected the notion that the cultural phenomenon was associated with a single population. In Iberia, individuals buried with Bell Beaker goods were closely related to earlier local populations and shared little ancestry with Beaker-associated individuals from northern Europe (who were related to steppe groups such as the Yamnaya). The pots did the moving, not the people.

这已经开始了。尽管关于钟杯现象研究结果表明,古代不列颠人的遗传构成曾发过了深刻的变化,但它也否定了文化现象只与单一种群相关的观点。在伊比利亚,用钟杯陶器作为随葬品的个体就与当地的古代种群密切相关,他们在血统上与来自北欧,同样与钟杯现象相关的个体(这些个体与来自草原的人类群体有关,如Yamnaya人)只有极少的联系。迁移的是陶器,而不是人。

Reich describes his role as that of a ‘midwife’ delivering ancient-DNA technology to archaeologists, who can apply it as they see fit. “Archaeologists will embrace this technology and will not be Luddites,” he predicts, “and they’ll make it their own.”

Reich称呼自己的角色为“助产士”:他只负责将古DNA研究的相关技术提供给考古学家们,他们会按照合适的方式来使用。“考古学家将拥抱这项技术,而不会变成卢德分子【译注:工业革命初期,有名为卢德(Ludd),来自英国诺丁汉的纺织工人,因担心纺织机器的普及会使自己面临失业威胁,而以砸毁纺织机器的方式表达抗议。后世便用卢德分子(Luddites)指代因担心机器取代自己而抗拒新技术的人。】”,他预测说,“他们将让这项技术为自己服务。”

A stronger partnership

更有力的合作

Nestled in a sleepy valley in the state of Thuringia in former East Germany, the city of Jena has become an unlikely hub for the convergence of archaeology and genetics. In 2014, the prestigious Max Planck Society established an Institute for the Science of Human History there and installed a rising star in ancient-DNA research, Johannes Krause, as a director. Krause was a protégé of the geneticist Svante Paabo, at the Max Planck Institute for EvolutionaryAnthropology in Leipzig. There, Krause worked on the Neanderthal genome and helped discover a new archaic human group, known as Denisovans.

耶拿市坐落在前东德的图林根州一个沉睡的山谷中,虽然看起来不太可能,但那里已成为考古学和遗传学合作的一个中心。2014年,享有盛名的德国马普学会在耶拿市建立了人类史科学研究所,打造的研究项目成了古DNA研究领域里中一颗冉冉升起的新星,Johannes Krause为项目的领头人。Krause师从于莱比锡马普学会演化人类学研究所的遗传学家Svante Paabo。在那里,Krause研究了尼安德特人的基因组,并帮助发现了一个新的古人类种群——丹尼索瓦人(Denisovans)【译注:2008年发现于阿尔泰山的古代种群,已经灭绝,和智人、尼安德特人同属人属】。

Whereas Paabo was focused on applying genetics to biological questions about ancient humans and their relatives, Krause saw a wider scope for the technology. Before leading the Jena institute, his team identified DNA from plague-causing bacteria in the teeth of people who died from the Black Death in the fourteenth century, the first direct evidence of a potential cause for the pandemic. At Jena, Krause hoped to bring genetics to bear, not just on ‘prehistorical’ periods such as the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, where archaeological methods are the main tool for reconstructing the past, but also on more-recent times. Outreach with historians is still a work in progress, but archaeology and genetics are thoroughly embedded at the institute. The department Krause directs is even called archaeogenetics. “We have to be interdisciplinary,” he says, because geneticists are addressing questions and time periods that archaeologists, linguists and historians have been poring over for decades.

虽然Paabo专注于使用遗传学技术研究古人类及其亲缘类群的生物学问题,但Krause已经看到了这项技术更广泛的应用前景。在领导耶拿研究所之前,他的团队在14世纪黑死病受害者的牙齿中发现了鼠疫致病菌的DNA,这是黑死病病因的首个直接证据。在耶拿,Krause希望能把遗传学技术应用于更广的时间范围:不只是研究新石器时代和青铜时代这样的“史前”时期(考古学方法是构建这个时期图景的主要工具),还可以研究更近的历史。在耶拿研究所,与历史学家的沟通正在展开,而考古学和遗传学已经紧密结合在一起了:Krause领导的部门甚至被称为考古遗传学部。“我们必须是跨学科的”,他说,因为遗传学技术正在不断地触及考古学、语言学和历史学领域数十年来一直关心的疑问和年代。

Krause and his team have been heavily involved in the map-making phase of ancient genomics(he worked closely with Reich’s team on many such projects). But a study published late last year that focused on the transition between the Neolithic and Bronze Age in Germany won plaudits from archaeologists who have been dubious of the larger-scale ancient-DNA studies.

之前,Krause和他的团队一直积极参与古基因组研究中“路线描绘”的工作(在很多项目上他与Reich团队密切合作)。但在去年年底,Krause团队发表了一项关于德意志地区从新石器时代到青铜时代之间变迁的研究。这项研究甚至得到了那些对大规模古DNA研究持怀疑态度的考古学们家的赞誉。

Led by Stockhammer, who also has a post at the Jena institute, the team analyzed 84Neolithic and Bronze Age skeletons from southern Bavaria’s Lech River Valley dating to between 2500 and 1700 BC. The diversity in the genomes of cellular structures known as mitochondria, which are inherited maternally, rose during this period, suggesting an influx of women. Meanwhile, strontium isotope levels in teeth — which are set during childhood — suggested that most females weren’t local. In one case, two related individuals who lived within a few generations of each other were found buried with different material cultures. In other words, some cultural shifts in the archaeological record could be due not to massive migrations, but to the systematic mobility of individual women.

Stockhammer(他本人也在耶拿研究所供职)的研究团队分析了84件新石器时代和青铜时代的遗骨。这些遗骨来自巴伐利亚南部Lech河谷,历史可以追溯到公元前2500年至公元前1700年间。在这一时期,细胞结构基因,即线粒体基因的多样性明显上升。而线粒体基因是母系遗传的。这表明可能有女性涌入。与此同时,遗骨牙齿中的锶同位素水平——这在童年时期就决定了——表明大多数女性不是来自本地的。在一个案例中,相差不过几代的两个具有血缘关系的个体却被以不同的器物文化方式埋葬。换言之,考古记录到的一些文化转变可能并非来自整个人群的大规模迁移,而是来自个别妇女系统性的流动。

It is the prospect of more such studies that has archaeologists salivating over ancient DNA. In the near future, says Stockhammer, archaeologists will be able to sequence the genomes of all the individuals at a burial site and build a local family tree, while also determining how individuals fit into larger ancestry patterns. This should allow researchers to ask how biological kinship relates to the inheritance of material culture or status. “These are the big questions of history. They can be solved now only with collaboration,” says Stockhammer.

更多此类研究的前景让考古学家对古DNA垂涎三尺。Stockhammer说,在不久的将来,考古学家将能够对一个埋葬点所有个体的基因组进行测序,建立一个当地的家族谱系,同时也能确定个体在更大的族群谱系之中处于什么位置。这能让研究人员去探索生物学意义上的亲属关系,与器物文化或社会地位的继承关系之间是如何关联的。“这些都是历史上的重大问题。这些问题目前只能通过合作来解决”,Stockhammer说。

Another glimpse of this approach appeared in February on the bioRxiv preprint server. The paper explores Europe’s migration period, when ‘barbarian hordes’ filled the void left after the fall of the Roman Empire. In the paper, a team of geneticists, archaeologists and historians built family trees of 63 individuals from two medieval cemeteries in Hungary and northern Italy associated with a group known as the Longobards. They found evidence of high-status outsiders buried in the cemetery: most bore central and northern European genetic ancestry that differed from that of local people, who tended to be buried without goods —offering tentative support to the idea that some barbarian groups included outsiders.

这类研究方法的另一瞥出现在2月份bioRxiv的预印本服务平台上。那篇文章的研究对象是欧洲的大迁徙时期,即“蛮族部落”填补罗马帝国灭亡后所留下的空白的过程。在论文中,由遗传学家、考古学家和历史学家组成的研究团队为来自于匈牙利和北意大利的两个中世纪墓地的共计63人建立了家族谱系,这两个墓地都和伦巴第人【译注:大迁徙中日耳曼人的一支,起源于北欧,最后定居于亚平宁半岛北部,建有伦巴第王国】有关。他们发现了高地位的外来人被埋在该墓地的证据:这些人的中欧和北欧遗传学祖先与本族人不同,本族人一般不会和随葬品埋在一起——这支持了部分蛮族群体中包含外来人的假设。

Patrick Geary, a medieval historian at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, who co-led the Longobard study, would not comment on the research because it is now being peer reviewed. But he says that genetic studies of historical times, such as the migration period, carry pitfalls, too. Historians are increasingly incorporating data such as palaeoclimate records into their work, and will do likewise with ancient DNA, Geary says. But they share archaeologists’ fears that biology and culture will be conflated, and that problematic designations such as Franks or Goths or Vikings will be reified by genetic profiles, overriding insights into how ancient peoples viewed themselves. “These days, what historians want to know about is identity,” he says. “Genetics cannot answer these questions.”

Patrick Geary是新泽西州普林斯顿高等研究院研究中世纪的历史学家。他是上述关于伦巴第人研究的共同领导者之一。因该项研究尚处于同行评审阶段,故他没有做过多评论。但他讲到,对有历史记载时期例如迁徙期的遗传学研究,也存在一些陷阱。Geary说,历史学家越来越多地把诸如古气候记录之类的数据引入他们的工作中,而且也同样乐意使用古DNA帮助研究。但他们有和考古学家同样的担心,即生物学概念和文化概念可能会被混为一谈。基因研究能够把诸如法兰克人、哥特人或维京人这样并不准确的名称完全具体化、明确化,这会压倒那些对古代人们如何看待自己身份的见解。“目前,历史学家想要了解的是历史上这些人的身份”,他说,“遗传学无法回答这些问题。”

Reich concedes that his field hasn’t always handled the past with the nuance or accuracy that archaeologists and historians would like. But he hopes they will eventually be swayed by the insights his field can bring. “We’re barbarians coming late to the study of the human past,” Reich says. “But it’s dangerous to ignore barbarians.”

Reich承认,他的领域并非总能在考古学家和历史学家所喜欢的差异和精度内探索历史。但他希望考古学家和历史学家们最终能被这一领域所带来的洞见征服。“我们就是人类历史研究这一领域内后到的蛮族”,Reich说,“但忽视蛮族是危险的”。

翻译:scipioliu

校对:Drunkplane-zny

编辑:辉格@whigzhou comments powered by Disqus