Why Doing Good Makes It Easier to Be Bad

为何做好事更容易变得不道德?

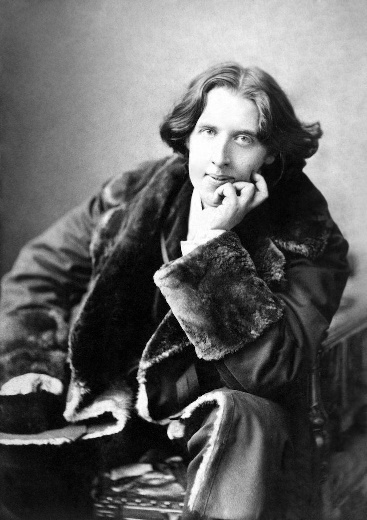

Oscar Wilde, the famed Irish essayist and playwright, had a gift, among other things, for counterintuitive aphorisms. In “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” an 1891 article, he wrote, “Charity creates a multitude of sins.”

著名的爱尔兰作家、剧作家奥斯卡·王尔德,其诸多天赋中有一项:反直觉的警句。在其1891年的文章《社会主义下人的灵魂》中,他写道:“慈善导致了许多原罪。”

So perhaps Wilde wouldn’t have been surprised to hear of a series of recent scandals in the U.K.: The all-male charity, the President’s Club, which raised money for causes including children’s hospitals through high-valued auctions, was forced to close after the Financial Times uncovered sexual assault and misogyny at its annual dinner; executives of Oxfam, a poverty eradication charity, visited prostitutes while delivering aid in earthquake-stricken Haiti, and were allowed to slink off to other charities, rather than being castigated for their actions; and ex-Save the Children executives Brendan Cox and Justin Forsyth stepped down from their roles at other charities, after allegations of sexual harassment and bullying toward junior female colleagues resurfaced.

所以对于最近在英国发生的一系列丑闻,王尔德一定不会感到吃惊:一个全部由男性组成、通过高价拍卖为儿童医院等目标募集资金的慈善组织“总裁俱乐部”,在被金融时报揭露其年度晚宴上的性骚扰及歧视女性丑闻后,被迫关闭;几名乐施会(旨在消除贫困的慈善机构)高管,曾在海地地震赈灾期间嫖娼。他们非但未因其行为被问责,还被允许悄悄转至其他慈善机构工作;在性骚扰和欺凌低级别女性同事的指控再次浮出水面后,前救助儿童会高管Brendan Cox 和 Justin Forsyth 从其他慈善机构中辞职了。

You might wonder how people who seem so good by occupation could be so bad in private. The theory of moral licensing could help explain why: When humans are good, it says, we give ourselves license to be bad.

你也许会奇怪,为何那些职业看起来光鲜的人,在私下却表现如此糟糕?道德许可理论也许有助于解释这种现象:作为好人,我们却给自己颁发做坏事的许可。

In a recent paper, economists at the University of Chicago reported that working for a socially responsible company motivated employees to act immorally. In one experiment, people were hired to transcribe images of short German texts and paid 10 percent upfront, with the remaining payment being delivered if they completed the transcriptions, or if they declared the documents too illegible to transcribe. When they were told that, for every job completed or marked illegible, 5 percent of their wages would be donated to Unicef’s educational programs, the instances of cheating rose by 25 percent, compared to where no charitable donation was offered. Cheating manifested in both workers not completing jobs (taking the 10 percent upfront fee and running) and also workers saying that documents were too illegible to transcribe (and so receiving the full fee).

在近期一篇论文中,芝加哥大学的经济学家们报告称,为承担社会责任的公司工作,会激发员工做出不道德行为。在一个实验中,人们被雇佣来抄写一些简短的德语文本图片。他们预先得到百分之十的酬劳,剩余部分则在完成抄写或报告文件无法识别后得到。当被告知每完成一次抄写或标记图片为无法识别后,他们收入的百分之五将被捐赠给联合国儿童基金会的教育项目后,欺骗行为立刻比无捐赠情况下上升了百分之二十五。欺骗行为在工人未完成工作(拿走百分之十的预付酬劳直接离开)和工人声称文本无法识别(因此得到全部酬劳)两种情形中都比较明显。

“The share of cheaters [was] highest when we frame corporate social responsibility as a prosocial act on behalf of workers,” the researchers, John A. List and Fatemeh Momeni, found. When the workers felt a greater sense that their own actions would lead to charitable donations, like Robin Hood, they in turn felt enough license to steal, essentially, from their employer to give to charity. “The ‘doing good’ nature of [corporate social responsibility] induces workers to misbehave on another dimension that hurts the firm,” List and Fatemeh concluded.

“当我们替员工做出决定,径自将企业社会责任设定为公益行为时,欺骗者的比例达到最高”,研究者John A. List 和 Fatemeh Momeni发现。当员工更明确地感到他们自身的行为将带来慈善捐助时,就像罗宾汉那样,他们反而确信拥有了为行善而盗窃雇主的“许可”。List 和 Fatemeh 得到结论:企业社会责任的“行善”特性,诱导了其雇员在其他方面做出伤害企业的不良行径。

When humans are good, we give ourselves license to be bad.

作为好人,我们却许可自己做坏事。

A parallel might be drawn between the transcribers cheating in order to give more money to charity, and the organizers of the male-only dinner hiring hostesses for titillation, in order to increase the appeal of the event and drive up donations. But there are problems using this theory to explain instances of sexual assault. Moral licensing only applies when the bad behavior can be self-rationalized as good—or, at least, ambiguous.

与前文抄写作弊以捐赠更多钱类似的是,仅男性参加的晚宴的主办方们,通过雇佣女侍者让参会者心情愉悦,以增加活动吸引力、促进捐赠。但使用该理论解释性骚扰案例也存在一些问题。道德许可理论只在恶劣行为可自圆其说或至少能模糊处理的时候才适用。

In a 2011 study, researchers at the University of Oklahoma asked students to complete mental math tests on a computer, simple arithmetic problems only involving numbers one through 20. They were told that they would be shown a math problem, and needed to press the spacebar to bring up the response box. If they failed to do that quickly enough, the answer would automatically appear, ostensibly due to a bug in the computer program, still in its piloting phase.

在一项2011年的研究中,奥克拉荷马州大学要求学生在电脑上完成一项只涉及20以内数字计算的心算测试。他们被告知将得到一道数学题,并需要按空格键以触发答题框。如果他们没能及时按键,答案将会自动显示,表面原因是尚在测试期的程序存在bug.

Students were given either 10 seconds or 1 second to press the spacebar, on the working assumption that, while students who failed to press the spacebar in 10 seconds were deliberately cheating, those who failed to press the spacebar within 1 second, could “rationalize their failure to do so as incidental rather than immoral.” After the test, the students were then asked how many times they had failed to press the spacebar quickly enough, thereby seeing the answer. The prevalence of lying was significantly higher amongst the 1-second group.

参与测试的学生有的被要求10秒内按下空格键,有的则是1秒。这种分组方法的假设是10秒内未能按下空格键的学生显然是刻意欺骗,而1秒内未能按下空格键的则有理由将其失败归结为偶然而非不道德。测试之后,学生被问到有多少次未能及时按下空格键,因而看到答案。在1秒答题组中,撒谎者的比例大得多。

But generalizing that moral licensing only occurs when bad behavior can be “rationalized” or “prosocial” overlooks the nuance of moral license theory, argues Daniel Effron, of the London Business School, who specializes in organizational ethics. “There are two versions of moral licensing theory,” he says. “One is the ‘moral credentials mechanism,’ which is more to do with rationalization. Basically it states, ‘I’ve done some good stuff. I’ve shown that I’m a good enough person. Now I can act ambiguously, because, as a good person, I know that my behavior is more likely to be good than bad.’ The other is the ‘moral credits’ mechanism, which works like a bank account. You do good stuff, you put a deposit in your bank account. You do bad stuff, you take a withdrawal. In that case, the bad deeds don’t have to be rationalizable.”

但是伦敦商学院专门研究组织道德的Daniel Effron认为,笼统的认为道德许可理论只适用于恶劣行为可被合理化或具公益性的情况,忽视了道德许可理论的细微差异。“有两种道德许可理论,”他说,“一种是‘道德资格理论‘,主要是关于行为合理化。基本上这种理论认为,‘我做了一些好事,证明了我是个好人,所以现在我可以做一些似是而非的事情。因为作为一个好人,我知道自己的行为更有可能是好的,而不是坏的。’另一种理论是道德记账机制,其运行原理如同银行账户。你做了好事后,在道德帐户中放入存款。做坏事的时候,就是取了一笔钱。在这种情况下,坏事便不需要合理化。

The latter version explains—though, obviously, does not excuse—the bad actions of Forsyth, Cox, and company. They had built up enough “moral credit” to justify taking some withdrawals, at least in their minds. This isn’t to say that the theory can determine or predict whether a good action will lead to bad behavior, Effron says.

后一种版本解释了——虽然很明显这并不是合理借口——在Forsyth, Cox身上和 企业中发生的坏事。他们存了足够的道德储蓄,因而有理由取出一些“存款”,至少他们自己这么认为。这并非说,这种理论能决定或预示一件好事是否将带来恶劣行为,Effron说。

He also stresses that the “charity sector isn’t any more vulnerable” to instances of moral licensing than any other sector. Humans are very good, he says, at finding reasons to be bad and making “mountains of morality out of molehills of virtue.” Studies have shown that trivial acts, including buying environmentally friendly cosmetics, can give consumers a moral license to behave badly. But, he adds, “You could make the argument that in the charity sector, you don’t have to work as hard to find your moral license for being bad.”

他也强调,慈善领域并不比其他行业更容易陷入道德许可困境。人类很善于找理由做坏事,并将一些细微的善行小题大做、标榜自我。研究表明,即便一些微不足道的事情比如购买环境友好的化妆品,都能够带给消费者道德许可,做出恶劣行为。但是,他补充道,“你可以认为,在慈善领域,人们不需要太努力就能找到做坏事的道德牌照”。

翻译:程鹏

校对:Drunkplane

编辑:辉格@whigzhou comments powered by Disqus